On Monday, a fellow DJ and I took a drive up to Richmond to see Liturgy perform live at the Richmond Music Hall.

Everything about the experience was surreal.

Richmond is a beautiful city. It’s a real city with a real city feel unlike that of Raleigh or Durham. Something about it felt historical, or perhaps I was just exhausted from the drive up and easily impressed by cool architecture.

Liturgy performed in Raleigh a couple nights before, but we’d decided to catch the all-ages Virginia show instead. It became something of an adventure, driving over a hundred miles to catch a live show in a small bar.

And by the time we headed back to North Carolina, we were both haunted by the majesty of what we witnessed at the Richmond Music Hall. Though the trip itself was tumultuous (read: exhausting, physically and mentally), it was ultimately worth it.

.gif from god

The first openers of the night, .gif from god are a 6-piece whitebelt screamo band. Based in Richmond, the band were comfortable on their home turf. It was interesting to see a “local” band play in an area that was foreign to me but familiar to many of the other attendees. There’s a special sort of liminality to such spaces.

I actually didn’t realize until they took the stage that the band’s members had been leisuring outside the venue when we arrived. That’s another thing I really like about smaller shows; you end up sharing the space with the artists rather than merely intersecting for a brief time and then moving on.

.gif from god was ravenous. Between the distorted guitar, brutal drums and virulent vocals, the room became something of a hornet’s nest. Even when the bassist snapped a string and was forced to briefly play without it, the band (and audience) never lost its energy.

Things became so unrestrained at points that several audience members took to the pit to gesticulate wildly in a frenzy of fists and feet. By the end of the set, my neck was sore and my heart was beating ferociously.

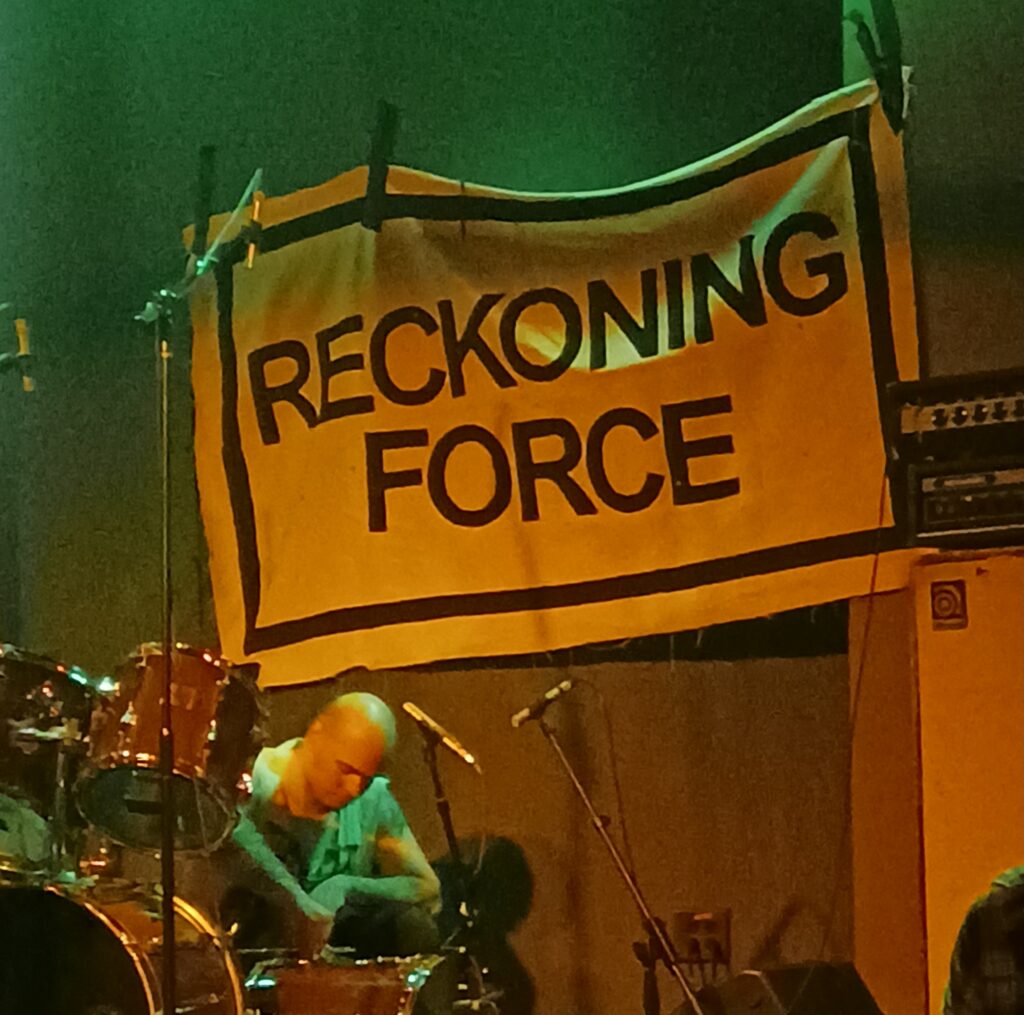

The HIRS Collective

The first thing I noticed about The HIRS Collective was the magnitude of amps they set up onstage. Like some kind of IRL tetris, the assemblage mystified the audience. I can remember hearing people behind me comment on the likelihood of long-term hearing loss following this set, and I was glad I’d brought my earplugs.

The HIRS Collective, based in Philadelphia, dedicate themselves to the defense and celebration of “any and all folks who have to constantly face violence, marginalization and oppression.”

They made this fact abundantly clear as they prefaced their set by dedicating their work to all trans women who exist, have existed and will exist.

The HIRS Collective delivered a unique and heavy performance, blending disco-inspired dance music such as Whitney Houston’s “I Wanna Dance With Somebody” with visceral metal vocals. As expected of a queercore band, The HIRS Collective was unabashedly hardcore and unafraid to have fun onstage.

I’m not sure if I will ever again have the privilege of witnessing a room of metalheads hesitantly headbang to Whitney Houston.

Liturgy

Liturgy is a “yearning, transcendental” black metal band from Brooklyn. Headed by vocalist and guitarist Haela Ravenna Hunt-Hendrix, Liturgy is both a musical project and a work of experimental, theologic art.

Upbeat strains of guitar and bass coalesce with Hendrix’s icy screams, creating something that punctuates the concept of music as an experience.

The show was ritualistic. Moving to the music was like moving in accordance with a divine heartbeat. The audience became a single entity, thrumming rhythmically like a complex piece of machinery, waxing and waning like seagrass buffeted by the tides.

Such is the effect of Liturgy’s music, self-described as “[existing] in the space between metal, experimental, classical music and sacred ritual.”