I’ve touched on the history of goth music on this platform before.

Considering the sheer volume of goth and goth-adjacent bands I cover on here, I think it’s safe to say that I’m fairly goth-focused. However, I’m far from an expert. When it comes to anything I’m passionate about, I consider myself perpetually learning and perpetually growing.

I’ve been long-familiar with the influence of punk music on the development of the goth subculture. Post-punk exists a staple of goth music (and my top genre of 2023).

What I wasn’t aware of, however, was the influence of black culture on early goth music. Once goth began to branch out from its deathrock roots, artists drew from numerous inspirations.

Among them, and arguably among the most important to the scene, was a genre I wasn’t even aware of until I started my research. This genre was not only important, but quite literally spearheaded the production of one of the most iconic goth songs of all time.

What is Dub?

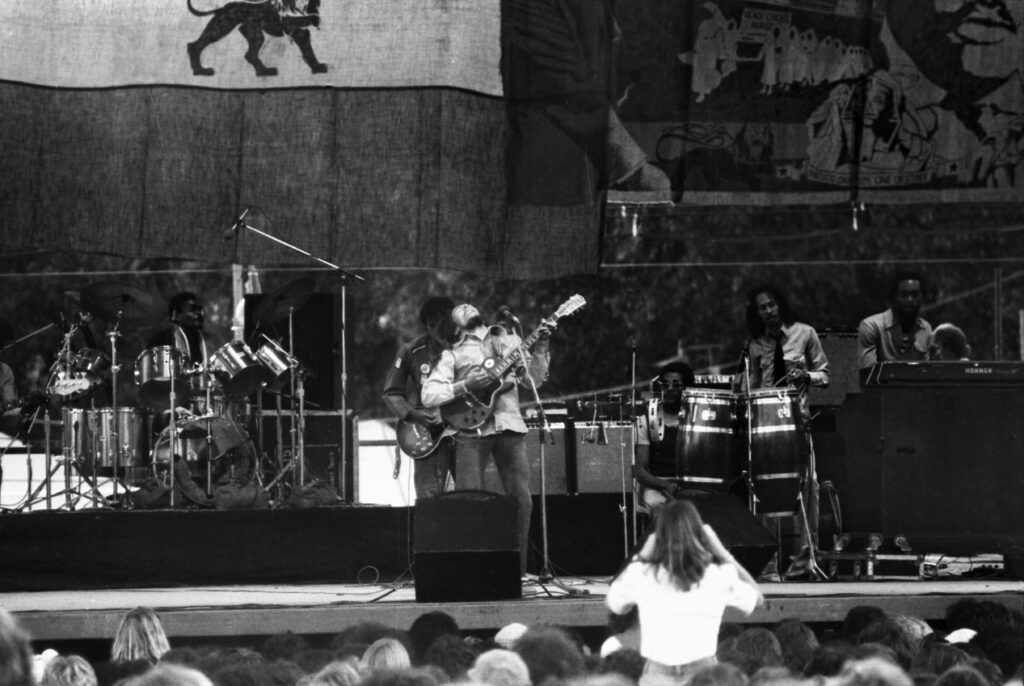

Dub emerged from the reggae scene in the late ’60s and early ’70s. In its earliest iterations, dub tracks were simply instrumental versions of reggae songs.

According to an article by MasterClass, artists would strip a track — usually of the reggae, ska and rocksteady genres — of its leading vocals and highlight bass and drums, occasionally mixing in their own sound effects.

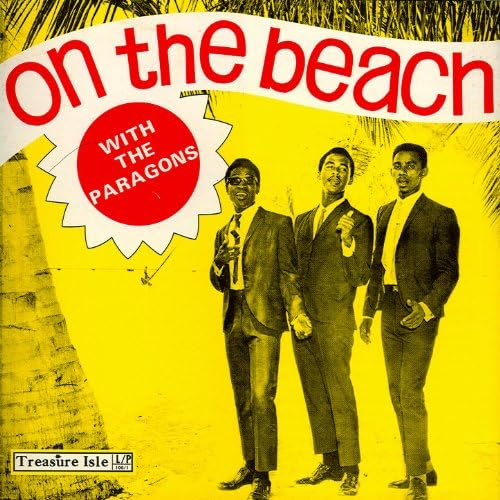

The “first” dub track was created in 1968 when the engineer for Treasure Isle studio accidentally pressed a copy of “On the Beach” by the Paragons without the accompanying vocal track. The mistake was a hit among Jamaican DJs, who improvisationally rapped (a practice called toasting) over the instrumentals.

Jamaican audio engineer Osbourne “King Tubby” Ruddock, roused by the track’s unexpected success, took to his mixing desk to experiment. Ruddock’s influence was instrumental in the growth of dub’s popularity and its spread overseas.

None of this would have been possible if not for the advent of multitrack recording, which allowed artists to strip down tracks in the first place. Other technological advancements in the recording industry would later prove instrumental in the development of the genre.

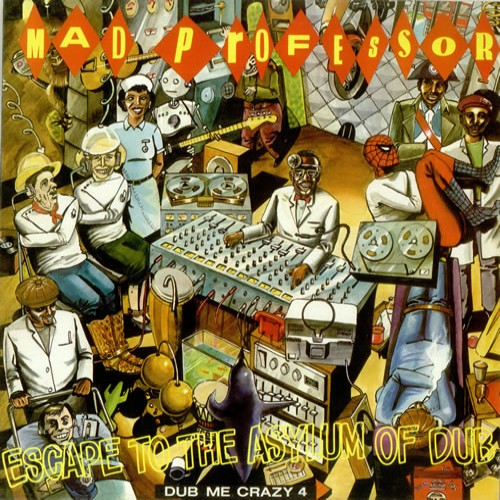

In the 1980s, a dub scene emerged in the United Kingdom with artists such as Mad Professor, Scientist, Jah Shaka, Adrian Sherwood, UB40 and Mikey Dread, who inspired acts like the Clash and the Police.

This influence can be seen among tracks like “Police & Thieves” and “So Lonely.”

During this time, electronic elements also made their way into the scene, leading to subgenres like dubstep and dub techno. Contemporary dub is considered an electronic genre as a result, often played in clubs and dance halls.

What’s that got to do with goth music?

The list of genres influenced by dub is multitudinous, featuring rock, post-punk, pop, hip-hop, house, techno, edm and many others.

If you’ve made it this far, you might be thinking: oh, dub influenced the goth scene through its relationship to post-punk. And while you wouldn’t be wrong, there’s an even more overt example of dub’s impact on the goth scene.

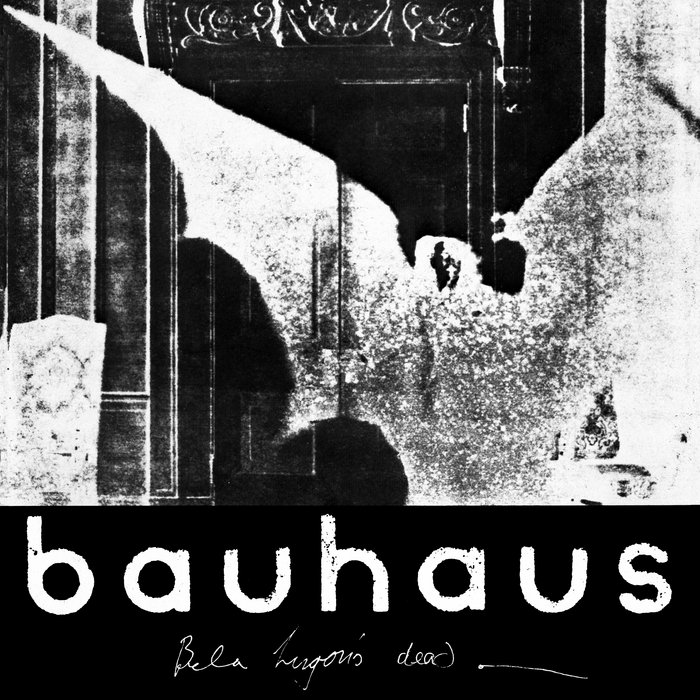

“Bela Lugosi’s Dead,” the debut single of Bauhaus, is widely considered to be the first gothic rock record. Released on Aug. 6, 1979, the 9-minute track served as a tongue-in-cheek tribute to the late Bela Lugosi, star of the 1931 film “Dracula.”

According to bassist David J in a 2018 interview with Post-Punk.com, dub and reggae were major influences in the song’s production.

“I mean, basically Bela was our interpretation of dub,” J said.

The sprawling instrumental beats and deep, preternatural bass of the song’s first half certainly echo dub’s style.

“It’s all very intuited,” frontman Peter Murphy said in a 2019 interview with Kerrang! magazine. “Very dub.”

Additional Reading

For some more info on reggae, check out “Chef’s Quick Bite of Reggae.”

For some additional reading on dub, check out “The Roots of Dub” by Kirt Degiorgio.