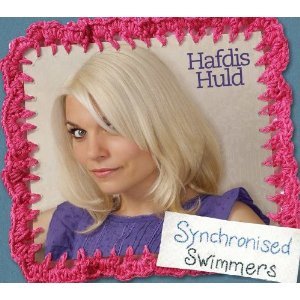

Aw. It’s nice. More like pop, with very sweet and gentle vibes. I probably would not put Huld’s Synchronised Swimmers (she spells it that way idk) on at a party, but I could appreciate it playing at my local bookstore. Perhaps it might do well in a quaint coffee shop as well. It definitely doesn’t rock, but Hafdís Huld’s talent is undeniable, so I’m not mad about.

All of these tracks sound nice. That’s really the best way I can describe them. Each track is cute and sweet and kind of makes me picture bunnies in the grass. Unfortunately, only a small percentage of my day could be backed by this type of music. It’s just soft. As I said, though, Huld pulls it off. The vocals really are beautiful, and you can hear the raw talent. The lyrics are also gentle on the ears and the mind. It’s hard to screw up soft words sung by a soft voice. Again – it’s NICE. Like I would maybe be friends with it, but Synchronised Swimmers is not marriage material. I wouldn’t be excited to commit to this album.

I think what brings it down for me is the way this entire album is produced. The finishing touches seem heavy-handed. Huld DOES have a beautiful voice, but these songs seem too polished. Gentle guitar with occasional piano and very soft percussion is basically Huld’s voice in instrument form. They clash. What I would really love to hear is Huld uncut backed by some soft acoustic sound – something not as shiny.

Basically – fine album with fine tracks. Maybe play it for your grandma while she sips some tea and you help her organize her file cabinet. Synchronised Swimmers is mild and unoffensive. Not mad about it, just underwhelmed. Ending this review with a shrug.

xoxo

your trusty music librarian