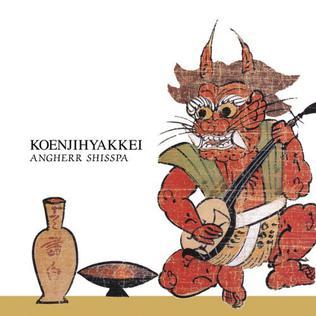

ALBUM REVIEW: Koenjihyakkei – Angherr Shisspa (2005)

BEST TRACKS: Rattims Friezz, Quivem Vrastorr

FCC Clean

LISTEN TO IF YOU LIKE: avant-garde, experimental, jazz

Before we get into this album in particular, it’s important to mention what “Zeuhl” is which is the musical genre this falls into. Born from 60s and 70s krautrock and coined by the band Magma’s constructed language Kobaian, there are only a handful of groups that have been able to consider themselves under this genre umbrella. As Pitchfork once put it, Zeuhl can be described by “sudden bursts of explosive improv and just as unexpected lapses into eerie, minimalist trance-rock.”

I would go on to say it is some of the hardest music to describe as it is to find. Koenjihyakkei is the side-project of Yoshida Tatsuya of Japanese Zeuhl group, Ruins, which is heavily influenced by 60s and 70s progressive music in general. This group also includes Aki Kubota (on vocals and keyboards) from another modern krautrock group, Bondage Fruit.

Koenjihyakkei’s “Angherr Shisspa” is one of the best albums to get into this genre with though.

This would be my own attempt to describe this wild album: experimental opera jazz with intensive complicated time signatures that boom and burst from huge orchestral and choral hits to single xylophonic beats. If you are looking for something like you’ve never heard before and crave the subtle balance between dissonant chord structures and ear candy, this is certainly an important listen.

The album has this way of being able to add this playful tone to something extremely avant-garde. Sometimes I feel when listening to this album that I am surrounded by a bunch of fairies that are screaming, dancing, and performing various rituals.

It is also another one of those albums that grows on you the more you listen to it, because it draws from so many different types of progressive and experimental music, it’s hard to keep track of it all on first listen. I’d consider this a hidden gem, simply given it’s status of being representative of a genre that does not get a lot of representation. Check it out if you want some new avant-garde music to listen to.

– Artzoid (Host of the Eclection)