Note to readers: this blog contains brief mentions of sex, pedophilia, arson, drug abuse, gun violence, involuntary commitment, and more while discussing music that covers such themes.

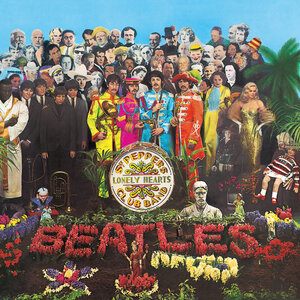

Listeners now may not recognize how old the concept of an album as a narrative device is. The history of the concept album is murky, the history of strictly narrative albums with characters, setting, and a climax are murkier. Some say, including literary review writers at the University of Connecticut, that “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” by The Beatles started the idea. Paul McCartney (alongside Boston-based radio station WERS) traces the Beatles’ inspiration to Frank Zappa’s “Freak Out!” released in 1966.

Fiona Sturges at The Independent goes further, saying that commercially available song collections including a broader narrative may have originated with Woody Guthrie in the 1940s. If you consider musicals or opera as part of this history, you can go back centuries. Even in spite of its unclear origins, the narrative album continues to be a significant and growing part of contemporary music.

In today’s music industry, where streaming is the unquestioned king, many have begun to question the need for albums as a unit of distributing music as a concept. While the album is no relic and is useful for both listeners and marketing professionals, there’s no need for audiences to listen to albums in whole if they can click out of the app and turn on something more stimulating at any second.

To be clear- I am not (falsely) claiming that shrinking attention spans and/or younger generations are “killing albums,” far from it, but it is clear that individual songs, or in the age of TikTok, 15-second clips, are the primary unit for marketing music in 2025. Even then, the album survives. Considering this, albums that present themselves as cohesive, or moreso, a heard, lived, felt *experience* are the ones that gain heavy traction in the age of social media. Narrative is a key way that artists capture an audience’s attention for the whole run time of an album. I personally have been persuaded by a friend sending me an album and saying “you HAVE to check this out.”

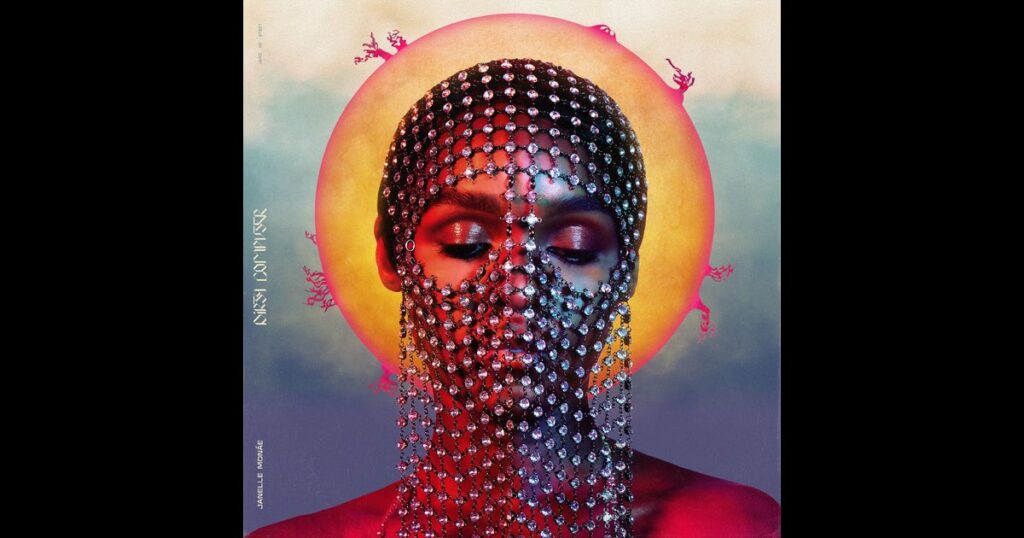

Mainstream artists like Kendrick Lamar, Janelle Monáe, Halsey and more have received critical and audience acclaim for presenting their albums as narrative, emotional, sensory experiences that are *felt* as much as they are *heard*. Some artists choose to embody “characters” of sorts with each new album, such as Janelle Monáe’s Android persona embraced in 2010’s “The ArchAndroid” and 2018’s “Dirty Computer.”

Albums like these are far from limited to the mainstream, with smaller artists like Sufjan Stevens, Aimee Mann and Ethel Cain (more on them later) among others gaining popularity for their music’s immersive features. In the case of Ethel Cain, the artist’s debut album “Preacher’s Daughter” has spawned a fandom of its own, with many becoming attached to the world of Shady Grove and beyond envisioned by the artist.

Considering the contemporary conundrum of the album as a mode of consumption, it stands to reason that many of today’s most enduringly discussed albums are those that create rich worlds that are immersively felt as audiences listen. Albums that “stick” most in current culture offer a unique experience when listened to in its entirety rather than as a collection of singles.

In the case of many albums, the ability to tell a somewhat cohesive story over the course of the contained songs can be a way for artists to express vulnerability regarding their own lives. The stories told through their music can highlight themes or emotions personally experienced by the artist. The act of storytelling is all about revealing a truth of some kind. In this case, creating immersive worlds and characters through music reveals thematic or emotional truths present in the artist’s life.

For example, shapeshifting art-rock establishment St. Vincent used her 2017 album “Masseduction” to explore themes of power, exploitation and social control through the album’s persona, which the artist herself named the “dominatrix of the mental institution.”

At the time of “Masseduction”’s release, the artist was in an overly-publicized relationship with model Cara Delevigne, which tended to overshadow the album’s release in the public eye. While many reporters tried to connect the “weeping Lolitas” (title track) and “crushes on tragedy” (“Sugarboy”) mentioned within the album, alongside the previously mentioned themes of exploitation and manipulation, to the artist’s real-world relationship and eventual break-up, they tended to miss the abundant satire of the media systems that allow for young artists to be cannibalized by a tabloid press.

The album’s lead single, “Los Ageless,” summarizes this perfectly. While the lyrics, ambiguous as they are, could be written about an elusive-yet-controlling lover, the song’s firm setting in “Los Ageless” and the singer’s habitual need to run from that place seems to suggest that the artist’s fame is under poetic scrutiny here. In viewing the album as solely a critique of St. Vincent’s relationship with Delavigne, one ignores the personal issues that came with the media spectacle surrounding their relationship. The album can even be seen as a warning, a prescient message about the relationship between exploitation and economic forces behind where one is told to direct their attention. Where the album’s promotional material and general aesthetics were geared towards embracing sexuality in relation to power, St. Vincent seems to promote the idea that sex is not the sole currency of exploitation, but invasive and prurient attention can be just as controlling.

Where “Masseduction” explores the brutality and carnality at the heart of fame within St. Vincent’s “Los Ageless,” Kilo Kish’s newest synthpop project takes aim at the ordinary indignities of an increasingly digital world. Each of the six tracks on “negotiations” is posited as some sort of love song or ode where the subject of affection can’t connect to their end of the receiver. Images relating to machinery, construction and data haunt the lyrics to Kilo Kish’s “digital emotional,” the lead single from the EP. She sings “Skyscraping / Pain killing / Shapeshifting / My mechanical heart beating for you” in the chorus, painting a picture where connection exists as a mechanized commodity.

In a following verse within the same track, she sings “I am so psychoanalytical / Pillowsoft and original / How did you nail that interview / Like, how did I get in to you / I don’t got the time to play / I check the data, I’m in first place / I can override your instincts.” Here she makes a nod to the source of her disconnection being competition (“I’m in first place”), corporate gamesmanship (“How did you nail that interview”) and even product placement (“Pillowsoft”), now ubiquitous aspects of life in the modern world. The loss of love, identity, and community Kilo Kish sings about throughout the EP can be traced back to the corporate, mechanical sterility imposed on average people in the artist’s conception of modern reality.

Promotional materials for the EP make her satire of technocratic office culture clearer. She sits like a queen atop a pillowsoft office chair in the cover for the single “enough.” For “negotiate,” Kilo Kish is seemingly overpowered by the weight and pressure of a stack of papers and binders taller than the artist herself! It may not translate the best to a text-based blog, but for years Kilo Kish has mastered the art of accompanying visuals that pair with her music. The breadth of her talent in this area is on full display throughout the music videos made for “negotiations,” where offices and sterile concrete walls form the backdrop to her art.

Trade concrete for warm-toned wood paneling, yellowed carpets and tense Southern humidity and you’d get a taste of the aesthetic qualities associated with Ethel Cain’s debut album. The North Florida native has had a huge following growing around her since the release of Americana-pop-rock hybrid “Preacher’s Daughter” in 2022. While she released a few EPs in the years before “Preacher’s Daughter”’s release, her first full-length album has (with the assistance of a few of its songs gaining steady popularity on TikTok in the last few years) launched her into indie fame.

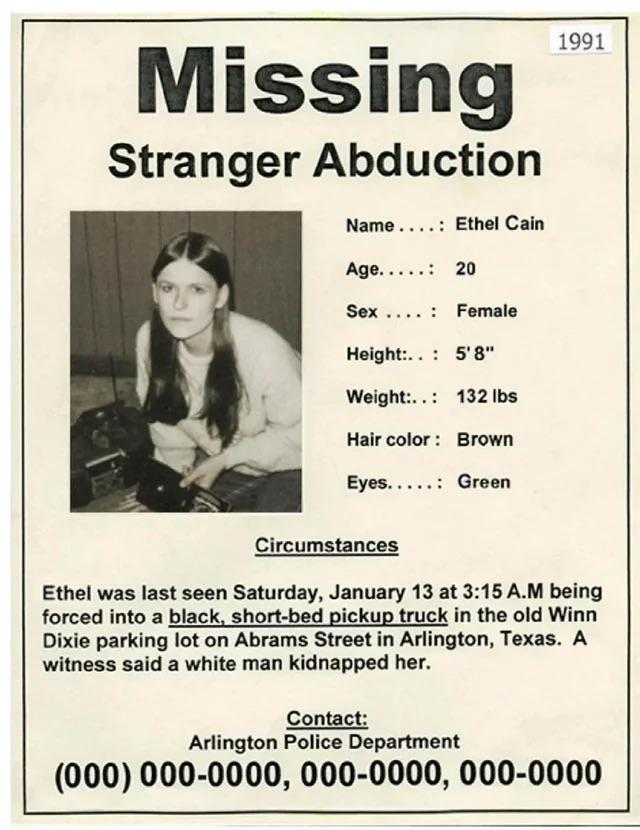

Ethel Cain’s debut certainly defines the kind of immersive, storytelling album that listeners have been clamoring for in recent years. Set in 1991, “Preacher’s Daughter” follows the titular character Ethel Cain as she is dealt blow after blow in her hometown of Shady Grove, Alabama, her escape from her old life, and her series of climactic tribulations and eventual disappearance in the American West.

While in Shady Grove, Ethel recovers from feeling abandoned by her former lover, Willoughby Tucker (“A House In Nebraska”), in a powerful ballad to lost love and the life that it offered her. More is revealed about her family in “Family Tree” and “Hard Times,” two unforgettable movements in the album which add detail to the backdrop of Ethel’s difficult young life.

Eventually, Ethel meets a man named Isaiah who promises her opportunity, sex and freedom if he joins her in the West (“Thoroughfare”), and feeling that she has gotten what she can from her life in Alabama, she follows him into unknown landscapes. Things turn more directly violent in “Gibson Girl,” and while I won’t spoil the rest of the album, I will say that “Strangers” and especially “Ptolemaea” will not leave your mind at any point soon.

Ethel Cain has announced that she will release a collection of demos from the album under the title “Willoughby Tucker, I Still Love You” later this year. In addition to this, she hopes to expand the world she created for “Preacher’s Daughter” by releasing more albums exploring Ethel’s family under the titles “Preacher’s Wife” and “Preacher’s Mother.”

The artist has not limited herself to working within this universe, however, as earlier in 2025 she released ambient mixtape “Perverts” to acclaim. For Perverts, the many tracks on the album explore isolation, shame and perversion alongside other themes. The visuals associated with “Perverts” are darker, and the album’s sound goes in the same direction.

For “Punish,” the lead single from “Perverts,” Ethel Cain wrote that “the og concept for perverts was a character study about different “perverts,” inspired by reading knockemstiff. a sex addict, a pedophile, an arsonist, a sedative addict, etc… punish is about a pedophile who was shot by the child’s father and now lives in exile where he physically maims himself to simulate the bullet wound in order to punish himself. at least that’s what i had in mind when i wrote it. the song can be whatever you want it to be.”

Ethel Cain’s exploration of isolation, violence and perversion in “Perverts” still highlights ways in which shame and guilt are enforced on the body in a very physical sense. Artists use stories like these to explore broader societal ills and reactions to them. The most recent album released by Aimee Mann, “Queens of the Summer Hotel,” presents a vastly different soundscape to Ethel Cain’s work, yet the thematic exploration of America’s recent history, methods of marginalization and the imposition of shame on people is similar.

“Queens of the Summer Hotel” began as Aimee Mann was preparing to write a musical recounting the events of “Girl, Interrupted,” a 1993 memoir by Susanna Kaysen later adapted into a film starring Winona Ryder. The memoir focuses on the involuntary hospitalisation of a young Susanna Kaysen in the 1960s. “Girl, Interrupted” was acclaimed for its open discussion of taboo mental health issues and honestly depicting the inner lives of young women within such a marginalizing and alienating environment.

Aimee Mann is no stranger to musical adaptation from film, having been nominated for an Oscar for scoring the 1999 film “Magnolia.” With “Queens of the Summer Hotel,” it was different, not just because this was an adaptation of a book rather than a film, but because this project was written for a production that was out-of-production, no “Girl, Interrupted” musical has been made yet. With this, Aimee Mann was free to add a new amount of own personal thoughts and feelings in addition to the story that originates in Susanna Kaysen’s book.

Aimee Mann approaches “Girl, Interrupted” by highlighting the setting of the original, largely being a mental institution in 60s Massachusetts, in the aesthetic composition of the album as well as through cultural references in the songwriting. One song from the album is literally called “Robert Lowell and Sylvia Plath,” referring to two poets associated with the 1960s confessional movement who had experience being committed in the era. Less obviously, the album’s title is taken from a poem by Anne Sexton, who had been institutionalized at the same hospital that Susanna Kaysen was at during the period depicted in her memoir.

Referencing culture from the era which inspired the album’s source material grounds it in a backdrop which recalls a different time in the history of psychiatry. Aimee Mann’s personal relationship with psychiatry is not a public affair, yet she was clear in mentioning during an interview with Variety that psychiatry, especially claims revolving around “hysteria,” is a sore place in conversations about misogyny in the medical industry.

The artist offers hope on the subject through the album’s final track “I See You,” where a force can see the faces and experiences of those struggling most and offers them undiminishable faith in community and understanding. As a verse in the track goes, “People get crushed and broken / People lose and they grieve / But I see / And I believe.”

As described, artists like Ethel Cain and Aimee Mann use their music to explore aspects of life that continue to affect people to this day. The album’s stories are about people quite different from the person singing, characters from a different part of history, yet singing their story gives a voice to unheard corners of society. On a different hand, there are artists who tell stories about themselves in an unmistakably personal, vulnerable manner to relate with and give visibility to people’s innermost lives.

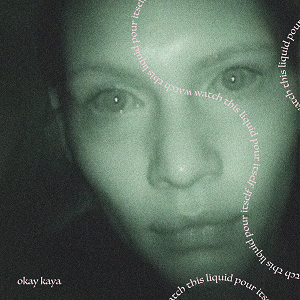

Okay Kaya’s thoroughly modern and effortlessly shapeshifting electronic album “Watch This Liquid Pour Itself,” released in 2020, is an intimate meditation on contemporary romance, maturity, overstimulation, the limited joys of giving up and vegan ice cream. Over the course of the album, Okay Kaya embraces a format reminiscent of coming-of-age media, where a “Baby Little Tween” learns and grows to accept various challenges, through hospitalizations and sexual incompatibility, ending with growth, breakups and ramen.

“Overstimulated” was notable for the artist’s strong vocal presence and incredibly relatable depiction of overstimulation and anxiety, ending with the artist rolling over with confusion into “Psych Ward,” the most danceable song about hospitalization I’ve ever heard, about the simple freedoms found in a mental hospital. Later, “Asexual Wellbeing” presents a thumping confession, where in the chorus the artist proudly chants that “Sex with me is mediocre / But I can give you asexual wellbeing,” hoping to find joy in connecting through other means.

The last half of the album is marked by a thematic turn in “Mother Nature’s Bitch,” where the speakers vows to approach life with a more accepting outlook, fully aware that this makes them seem like they are giving up. In a later track, this is called “Givenupitis.”

Eventually, after a beautiful song sung in Norwegian, “Stonethrow” presents the artist’s insecurities laid out clearly for their partner, where they claim they’re “only joking / When I mean every word I say.” “Stonethrow” seems to be a breakup song, where she calls herself a rock that can no longer fit in the hands of another, even if she still feels “a stonethrow away.”

The following track, “Zero Interaction Ramen Bar,” is a less than two-minute long song that gives the singer room to lament the loss and turmoil that they’ve been stuck with throughout the album. Nothing but the artist’s voice and faint bells are heard throughout the track. Okay Kaya sings about how her former lovers found her and her music endearing in the past, but chose instead to “leave me all alone with / My parasite and I.” The album closes with her singing a lengthy, stressed note from the perspective of the parasite, a fitting and deeply emotional sound she’s been yearning to release, followed by the artist relievedly whispering “oh, f*ck.”

Okay Kaya has released a few more albums since “Watch This Liquid Pour Itself,” with her sharp and relatable songwriting talent present across all of them. Her ability to turn simple, strikingly modern phrases and images into emotionally packed symbols of growth is powerful. What can come across to some as reaching for relatability appears to be an achingly self-aware reflection on modernity and connection. Overall, though, Okay Kaya’s strength as a songwriter comes from her ability to turn literal aspects of her life into a compelling story. When confronted with the stress, confusion, and awkwardness that comes with living in today’s world, she turns it into one hell of an album.