It’s all fun and games till the jock comes off…

The year was 1974, and the good old sport of the Great North was bloodier than ever.

From semi-pro to the NHL, fists swung with the same if not more force than the mighty stick.

And no one more personified small-time, minor league Old Time Hockey quite like the Johnstown Jets.

Where We Started From

Based in Johnstown, PA, the Jets were known to be some of the nastiest players to take the ice.

Tough but talented, they beat the opposition into submission just as frequently as they out-scored them.

However, amongst their ranks are four men who would help take the Jets from NAHL darlings to legends of the silver screen: Ned Dowd and the Carlson Brothers, Jeff, Jack and Steve.

While Ned Dowd and the Carlson brothers were the origin of so many hockey-hijinks that made it on film, it was his sister Nancy Dowd who put pen to paper and crafted what we would all come to know and love as “Slap Shot.”

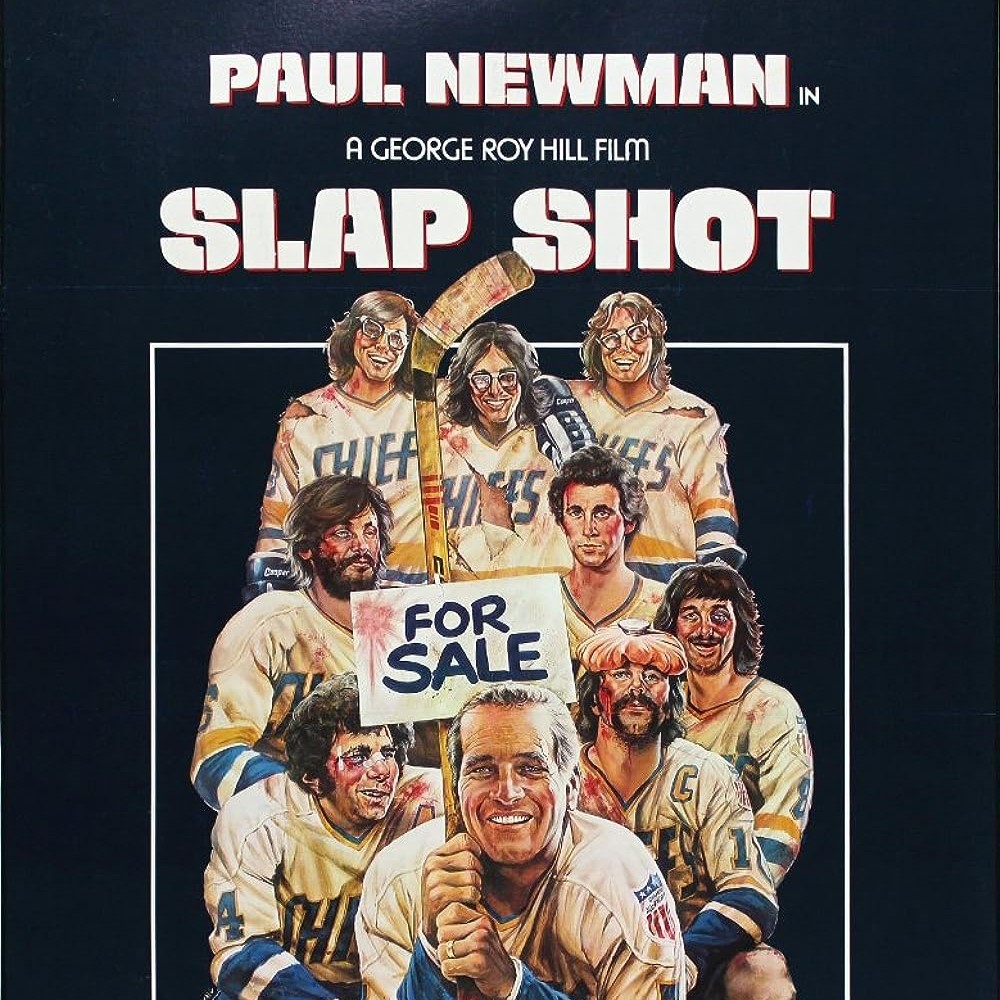

Written by Dowd and directed by George Roy Hill, the 1977 film “Slap Shot” follows minor league underdogs the Charlestown Chiefs in a bid to go out with an end-of-season blaze of glory, the failing team resorting to dirty plays to win the affections of their fans.

It’s simple math; a fist to the face puts butts in seats.

The aforementioned Ned would appear in the film alongside two of the three Carlson brothers, Jeff and Steve, as two-thirds of the fictitious “Hanson Brothers.”

Jack, was unable to participate in filming due to contractual obligations with the Edmonton Oilers.

Instead, he was replaced with Dave Hanson who played the fictional counterpart to Jack.

While all three “Hanson Brothers” would have respectable pro careers, Jack Carlson became a legend in his own right upon the ice, totaling 1111 penalty minutes across 508 combined professional games within the WHA and NHL.

With most of the on-screen antics pulled from real-life incidents on the ice, the film has garnered a somewhat checkered reputation within hockey circles.

The official NHL company line suggests that’s not what hockey is about and never has been, but, player commentary suggests it’s a mainstay on busses and charters.

Do with that what you will.

On the other hand, within the minors the film has garnered the singular reputation as “the bible.”

Once again, do with that what you will.

A Legacy Worth Leaving

But beyond goons, the film is funny and crass and violent and most definitely a product of its time.

I’m almost tempted to place it on the list of “films that couldn’t be made today” but beautiful blue-eyed Canuck Jared Keeso sought to prove that thought wrong.

In modern comparisons, you wouldn’t have the TV show “Shoresy” without “Slap Shot,” but as I said before, it’s simple math: fist + face = butt in seat.

Bawdy and brawny, yes, but really at the core of both pieces is the love of a good old hometown hero; something for people of a failing town to fall behind when times are tough.

Much like the fictional Charlestown of the film, the real Johnstown was troubled from the turn of the century by flooding.

Nicknamed “the flood city,” Johnstown saw the flood of 1977 bring about the demise of the Jets during the off season, coinciding with the inevitable fold of the NAHL.

Yet, their story lives on decades further than I would bet any player ever thought a rinky dink minor could all because a sister took stock in her brother’s stories.

Now, that being said…here’s some songs to start a fight to, in the name of Old Time hockey, of course.

Bodhi’s Best:

“The Stripper” by David Rose Orchestra

Big, Bawdy and indisputably raunchy, “The Stripper” is a mainstay on burlesque stages across the globe, but Michael Ontkean brings the lascivious display of the stage to the ice in protest to the so-called goon-like antics of his team.

Beyond violence, “Slap Shot” is without a doubt a film about sex. The players are hounded by (and hounding) groupies, a housewife is turned into chirp-material for experimenting with other women while her husband is away on the road, and a couple’s marital tensions underscore Ontkean’s Ned Braden’s real emotional strife throughout the film.

In the final knock-down drag out against the fictional Syracuse Bulldogs, Braden makes a show of his own with a striptease worthy of even Ms. Gypsy Rose Lee.

While blood spilt rips the crowd into a frenzy, it’s the playful sensuality of the strip that shocks the masses.

It’s not until a high school marching band in the stands launches into a ramshackle rendition of “The Stripper” that the crowd finds their feet once again.

But then again, I’ve always thought there were two “f-words” in the English language…but I’ll leave you to figure out what those are.

“Trampled Under Foot” by Led Zeppelin

In a movie that’s equal parts sexual as it is violent (at least by 1970s standards), what’s better than a song that serves up both in equal doses; you can woo your woman and win a fistfight all in one fell swoop.

“Trampled Under Foot” is the fifth track off Led Zeppelin’s 1975 album, “Physical Graffiti.”

A play on Robert Johnson’s 1936 song, “Terraplane Blues,” “Trampled Under Foot” uses cars as a metaphor for you guessed it, sex.

But, that’s not to say it is also one of what I would consider one of the band’s toughest tracks throughout their discography.

It’s one those songs that comes right out from the stereo, grabs you by the throat and refuses to let up.

From Jimmy Page’s absolutely ripping chords to Robert Plant’s screeching wail it’s breakneck in every sense of the word.

In Bodhi’s words, a real romper stomper.

“The Hockey Song” by Stompin’ Tom Connors

Speaking of stomping, what good is a hockey set if I don’t have at least one song directly referencing the game?

Because for all the fighting and the…other f-word I’m not legally allowed to say, I deeply love this sport and I especially love the smaller teams.

From NC State’s Icepack to the Winston Salem Thunderbirds all the way up the the Carolina Hurricanes, I think there’s something so absolutely beautiful about this rough-n-tumble, raggedy damn sport.

Maybe it’s the fans, maybe it’s the on ice celebrations, maybe it’s because I’ve got a weak spot in my heart for scarred and toothless men, I don’t know.

But what I do know is the collective energy of being in the old barn or the stadium is only paralleled to the most energetic concerts and even then, it doesn’t always match up.

Simply put, it brings people together in a way I’ve never quite seen before, and I think that togetherness is something we as human beings need more than ever.

Did you miss the show? Find it and so much more here.

Want to listen now? Listen Here.

Reel-To-Reel airs on WKNC 88.1 FM HD-1 at 8 a.m. Friday Mornings.