If youre looking for a digital kiki, some parasocial comradery or takes on current events,

Give these a try–

If youre looking for a digital kiki, some parasocial comradery or takes on current events,

Give these a try–

The NC State Fair

photos by Evie Dallman

I googled something once

The value of the humanities can be described in a multitude of ways, one in which I’ve adopted is the notion that engaging with culture, communities and the arts, interrogating their forms, can help us better interrogate our own lives in this same manner as the classics and the acclaimed.

So I was crying over the death of Socrates studying for my ancient Mediterranean history class and something stood out to me.

“this charming man”, this charming man you say…

Acclaimed artistry, The Smiths. As I grow up I move from listening to them in nostalgia for my mother’s taste and her adolescent soundscape and now nuzzle my way into the songs.

It’s quite odd to grow with a song, to fit yourself, your narrative and snapshots slot into anothers lyrics, someone else’s life.

The 15th year of Raleigh’s homegrown Hopscotch celebrates a diversity of music experiences and cherishes Raleigh’s flair. It featured day parties, discussion panels and genres covering metal to country and events involving the city’s businesses such as galleries, restaurants and shops.

Frank Meadows, Day Party Coordinator and Co-Head of Dear Life Records spoke about the festival’s origins and impact.

“Hopscotch is named in reference to Raleigh’s grid structure and the ability to navigate between venues and sets…You can see a lot of everything if you’re willing to jump in and catch 10 minutes and then head over to other stuff,” Meadows said.

“The format is conducive to exploration and putting a lot of different organizations, bands and music performers in the same pool.”

Part of Meadow’s job also includes working with local organizations in hopes of increasing the accessibility and local representation in Raleigh. “We put the pieces together for hosting free and public events that highlight what people are doing in Raleigh on a day to day basis,” Meadows said.

For example, Black + White Coffee Roasters hosts ‘Roadkill Angels Day Party’, showing bands like bedrumor, Foxie Kills, Lily Flower. Experimental pop group Entrez Vous joined Kit Mckay, Featherpocket, and Kenny Wavinson at Wolfe & Porter’s “Indie Twang” Hopscotch Day Party. This world building and pockets of parties is a main component to Hopscotch’s charm.

If you follow the sound, Hopscotch is the perfect venue to taste a little bit of everything and find a new interest. Meadows elaborated on how Raleigh’s layout specifically supports this kind of festival. “One of the cool things about it is that you get to be out in Raleigh on a really lively weekend and can take a break and get a drink somewhere nice,” Meadows said.

This emulsification of various scenes lends to a vibrant weekend in downtown Raleigh, spanning into venues down the ways and even in the post and upcoming days as the community engages in kickoff parties Wednesday and more music Sunday, invigorated by a beat carried through the streets.

Meera Mehta, senior in Business Administration with a concentration in IT and marketing, says “I think it brings together a sub genre of people that would have never met under the same context, other than Hopscotch”.

This lively weekend and its disposition was something I had Michael Whittington, Senior in Statistics speak on, to which he said “I would like to see the percentage of hopscotch goers that are above the age of 30 years old.”

This trend analysis was elaborated on by NC State graduate in International Relations, Avery Pardue in regards to cultural and consumption based content saying “I would like to see a 30% increase in IPAs. I would like to see a 30% decrease in man buns and skinny jeans”.

This playground for fashion, culture, community and musical artistry lends to all sorts of people and works to support Raleigh as a community and cultural hub as discussed by Neptunes founder, on his discussion panel and film screening of local film ‘The Great Cover Up’ about King’s Cover Band show series.

The documentary and discussion panel highlight how events, continual experience creating and the annotation of that culture through the documentary was purely sourced through community. This emphasis on supporting creativity and a positive feedback loop of structural support in communities such as Raleigh is the running throughline of what Raleigh aims to do in its next stages of development as we see industry and politics evolve.

This throughline runs central to Hopscotch’s mission, which aims to integrate independent musicians and connect them with different artists and opportunities. Meadows expands, “All genres, from hip-hop to rock and roll to jazz to punk to metal to experimental and beyond. If there’s a common denominator, I’d say almost-if-not everyone releases music on a non-major label…”Public Enemy was the headliner of the first Hopscotch, which represents a very concerted effort to include underground and independent music”.

Catch you there.

Copenhagen’s Shinyhunt, interviewed by eviedall for WKNC

On making music as a couple

Frederik

“we started making music together because we make it in our home and listening to each other’s songs, we started adding stuff to each other’s songs, and then ‘Joyland Grow in Me’ became a really explorative record for us, because we didn’t know what sound we wanted to explore further, then we found it on that record. ‘Sea Salt Ice Cream’ is kind of like an an extension of what sound resonated the most between us from that record.”

Signe

“it has been another kind of language to have with each other, a way of getting to know each other and finding a deeper way of communicating with each other.”

Photos by eviedall.

Good Bad Happy Sad and found sound

The band Good Bad Happy Sad resembles a trance trip state in which sound merges behind found and curated, meshing conversations and tunes and timelines pulling on simultaneous explorations of different genre associated sounds.

“… for hours, days, or weeks at a time”

sedative sounds

Martin Beck’s exhibit at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum reinvigorates an old story and pokes at sound as a medium we move through and with, often without recognition.

Informed by the “environments” records in the 1970s, which aided in synchronizing work, sleep and relaxation, Beck works to understand our industrialized soundscape as it relates to neuroscience, behavior, our internal worlds, and of course: capitalism.

His title ‘for hours, days, or weeks at a time’ is reminiscent of the infinite lull, hum, and buzz we find ourselves engrossed in a hyper produced world, whether self-selected or accidental background noise.

The exhibition uses sound, drawing, video and installation to curate a lively yet sterile environment, controlling the chaos we find ourselves drenched in our day to day worlds.

“[I]t’s what happened to your fore parents and other people. And that’s what makes the blues.”

John Lee Hooker

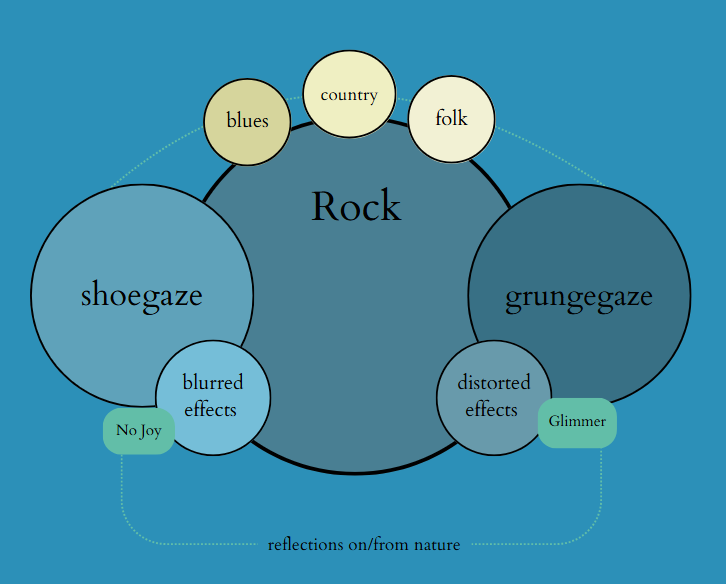

Last year I went to Pond’s concert in Asheville, the day after in a town over we told a barista and he asked if they are ‘like shoegaze’; I said yeah thinking ‘shoegaze’ was the band Slowdive.

A year later I’ve delved into shoegaze and most notably grunge gaze, a la Wisp opening at Slowdive, interviewing New York’s Glimmer, reddit acclaimed shoegaze No Joy and listening to California’s Midrift, Arizona’s Glixen and Connecticut’s Ovlov.

These genre evolutions from Rock, with its roots respectively in Blues, Country and Folk, reflect conversations between industrialization and balance with nature and distortions organic and synthetic as well as personal and collective struggles.