This is part three of a series on the birth of avant-garde music. You can read this article alone or view part one here.

Last time we covered some music that wasn’t very good, this week we’re going one further to discuss some music that isn’t very music. Yup, in the 1940s and 50s classical music lost its mind and the boundary between high art and experimental was all but erased. Hope you like four minutes of utter silence and naked people playing the cello with guitar picks, because it’s time to talk about John Cage and Fluxus.

So, my main criticism of modernism was that it didn’t untether itself fully from the classical tradition. This was a fairly common criticism, especially as early modernists like Schoenberg who retained some sense of harmony gave way to incredibly complex, mathematical composition methods like Stochastic Music and Markov Chains. Classical music was rapidly turning into a race to the bottom for who could create the most mathematically intricate yet aesthetically bankrupt composition method. A change was sorely needed.

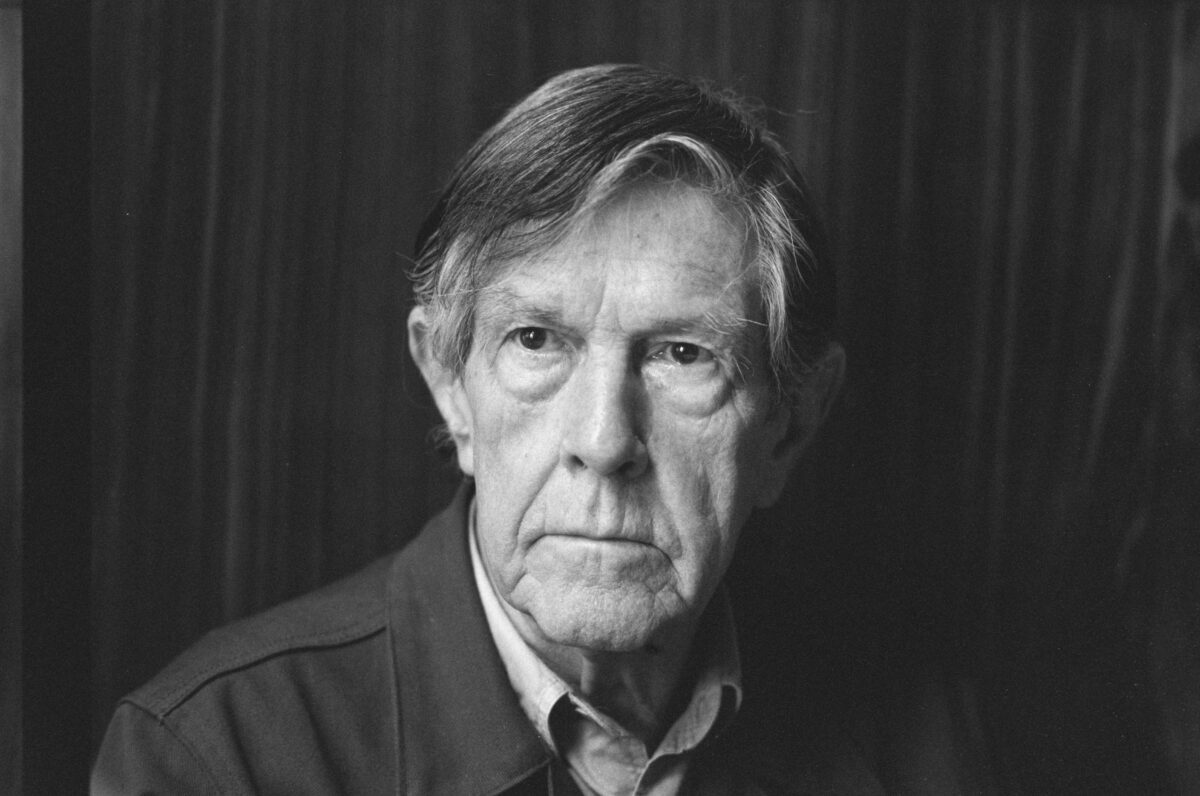

John Cage

Going chronologically, we’ll start with Cage. John Cage—not be confused with his student and Velvet Underground member John Cale—was a composer, but his legacy as a philosopher and theorist is more formidable. He hasn’t left a significant body of work, but his method for artistic exploration is effectively the benchmark for what we call experimental music today. Devised with his husband Merce Cunningham and artist/nun Sister Corita Kent, John Cage developed an approach to music that resembled “purposeless play,” emphasizing experimentation as an activity without a preordained goal. Unlike his teacher Schoenberg, Cage didn’t come into composition with a specific end in mind, instead focusing on the process of composition as a way of discovering new sounds.

Cage’s most famous piece is, unfortunately, and fittingly, “4’33’.” If you aren’t familiar, it’s literally just 4 minutes and 33 seconds of silence “played on piano.” This has become a kind of ur-example of laughably pretentious art, a reputation that is probably deserved, but hear me out. You are a Manhattan aristocrat going to see the world premiere of a piece by the most famous classical composer in America. You pay a lot of money for fancy clothes, tickets, wine, and show up at the theater. A pianist sits down to play music, he takes a while before he starts the piece. He’s just sitting there. Waiting….hold up.

Yeah, so “4’33’’ was perhaps the greatest troll attempt in classical music since Handel’s Surprise Symphony. More accurately, it was a piece of performance art. The light contempt for the high art market is implicit. This brings us to another performance artist who successfully trolled a pompous art market: Yoko Ono.

Fluxus

Now, I have written about Ono’s music at length, so I’ll be brief here as you’re likely already familiar anyways. Your average Beatles fan could tell you Ono was a visual artist before her transition to music, but less well known is that she was extremely successful, and the movement she was a part of, Fluxus, was already experimenting with sound.

Fluxus was a movement centered on making art that could either be replicated and recreated by anyone at any time or was explicitly a one-time phenomenon uncapturable in a gallery. The linking thread being a disgust with capitalist commodification of art, and a dislike of the “high art” market. Fluxus artists used Cage’s technique for a variety of things, creating one-sentence instructions for doing a performance art piece to be performed by anyone, experimenting with unusual sculptural objects, or just kinda messing around.

I bring up Fluxus, a non-musical movement, both to explain why visual artists will play such a big role in our last segment and to show that Cage really did make a conceptual leap forward. We’ll cover the link between Cage and modern popular experimental music next time (I may have already given it away though) but it’s important to understand that experimental is not a genre tied together by specific sounds. The modern machismo “Xtreme Music” reputation of noise and metal have their own histories, but experimental music is ultimately a process of finding what sounds seem novel and interesting to you.

Outsider Music

As an epilogue (dang this article is too long) I’d like to briefly mention outsider music. Championed by a few French composers whose names are impossible to distinguish, outsider music was music made by people without formal artistic knowledge. Normally this included children, the elderly, the mentally ill, people from pre-industrial cultures, or the intellectually disabled. Now if that grab bag of unrelated groups seems a little exploitative, you’re probably right. The reason I refuse to name the composers associated with this movement is that I’m uncomfortable with them receiving the credit for music made by people less powerful than them, but the existence of outsider music demonstrates an important point.

The process of experimentation employed by Cage is not an enlightened invention, it’s the natural way humans make art. Pop/rock is not simpler or less advanced than experimental music, in fact, it’s the other way around. The music theory conventions that define mainstream music are highly complex, and themselves inherited from classical and jazz. Experimental music, by contrast, is created through play, and is only revolutionary because it’s really hard to unlearn the expectations of popular music once you learn them. So, when avant-garde music feels too dense or intimidating, it’s worth remembering that you don’t need to take it all seriously, especially if you don’t like it.