Welcome to America.

In the world of filmgoing, a phrase tinged with nostalgia tends to pop up frequently in conversation: “they don’t make them like they used to”. Like it or not, movies have changed.

Gone are the days where a sentimental, middlebrow-but-still-touchingly-original drama like “Dead Poets Society” could gross over $200 million, as these standalone stories have largely been replaced with multiverses, franchises, spin-offs, etc.

It seems the idea of an original artistic vision that sees large success has been lost to the past, and those passionate about film are wishing to go back. It makes sense, then, that we are seeing an uptick in movies that they “don’t make like they used to.”

Just two and a half years ago, Tom Cruise “saved movies” with “Top Gun: Maverick,” which felt remarkably like one “they used to make.”

A sequel in name only, there were no superheroes; no extended universe; no shock value, just Cruise doing his own stunts and almost getting himself killed.

Or in 2023, take “The Holdovers,” a film which I was sure was not going to be popular upon seeing the trailer–words I would quickly eat.

The Giamatti-led dramedy harkened back to those films like “Dead Poets Society,” right down to the grainy film aesthetic and Cat Stevens soundtrack. It felt like a movie you’d find on VHS in your grandma’s living room. And it was a hit, more than tripling its budget.

So it makes sense that this trend would continue in 2024, with the release of Brady Corbet’s “The Brutalist.”

If “Top Gun: Maverick” is a classic, scorching action flick and “The Holdovers” is a classic, bittersweet Christmas movie, then “The Brutalist” is a classic period epic. The most obvious comparison is “The Godfather,” both circling a three-hour run time, both examining the immigrant experience in America in the ‘40s and ‘50s.

As if the subject wasn’t old school enough, Corbet employed the use of VistaVision to shoot the film, a 35 mm technique used to shoot greats like “Vertigo.”

And did I mention there’s an overture and an intermission?

“Dead Poets Society” wasn’t enough for Corbet, he needed to go back to “Seven Samurai.”

My screening was equally as mystical as the magic behind the movie. I booked a whole afternoon to see this behemoth, and it just so happened to be the day Raleigh got its first snow in three years. Things were falling into place for a truly special moment at the movies, and this thought was well-justified by the opening scene.

A jaw dropping, staggering moment of rebirth: it’s 1947, and we follow Hungarian architect László Tóth through a tumultuous ship overflowing with hopeful migrants as a letter from his wife, Erzsébet, is read aloud. She has also survived the Holocaust and is safe. They will be reunited.

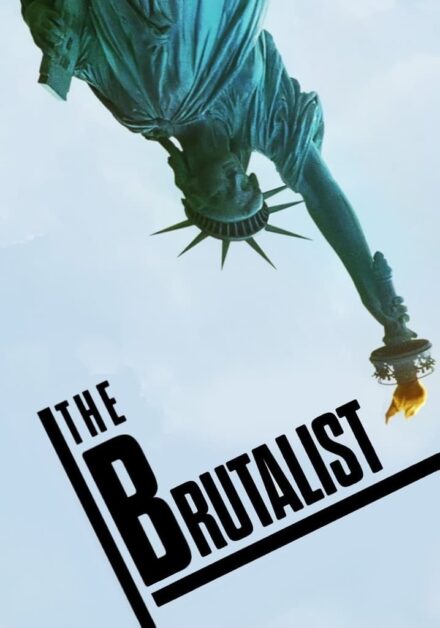

Daniel Blumberg’s grand, thumping score crescendos to a peak as László emerges from the ship interior and sees Lady Liberty.

We are seeing her through his perspective and as he looks up, she is affixed pointing downward, a fiery beacon symbolizing the American dream is inverted like the Cross of Saint Peter.

Nonetheless, he is elated.

As a standalone scene, it is about as perfect as you can get. Immediately, the tone is set: gargantuan, melodramatic and epic.

Corbet does have to follow up the stellar opening with another three-and-a-half hours of movie, though, and the bar is set quite high.

Part one is titled “The Enigma of Arrival,” and thankfully continues confidently with the quality established in the opening.

Tóth, portrayed marvelously by Adrien Brody, bounces between jobs including furniture manufacturing and coal mining before a former client, Harrison Lee Van Buren, approaches him with a project.

Van Buren is played by Guy Pearce in a career-best role, transforming into a character somewhere between the Monopoly Man and a forgotten US President.

The character is played with touches of Philip Seymour Hoffman, showing an eloquent and poised exterior that bubbles inside with something sinister.

Quickly, it is apparent that Corbet is deeply interested in playing with the dynamic between the lavish industrialist and the exploited immigrant. Like dolls, he places them in different vantage points — perspectives — creating a little diorama of 1940s America.

Van Buren and Tóth’s meeting is framed with Tóth atop a massive pile of coal and Van Buren below him. Van Buren has read up on Tóth’s work in Hungary and knows of his intellectual power. He is offering Tóth a way out of the rubble he finds himself in.

The premise for the rest of the film is established when Van Buren invites Tóth to a party at his estate and reveals he wants him to build a monolithic community center in honor of his mother. The stage is massive, with Van Buren announcing the plan upon the hill it will be constructed on.

Corbet frequently employs this technique of larger-than-life shots.

At his lowest, falsely accused of making a pass at and kicked out of the furniture shop by his cousin, Tóth is juxtaposed with monstrous manufacturing equipment at the coal mine. And with a spark of hope for the future, Tóth stands with Van Buren like ants atop the sprawling Pennsylvania hill.

These wide VistaVision shots not only add to the general grandeur of the film, but they highlight a central message: this is not just Tóth’s story, this is an arc lived by millions of immigrants coming to America.

Hundreds of Tóths could fit into some of these frames; this story has been lived and felt many times and will continue to be experienced in new, evolving ways. The atmosphere is almost Biblical, like this story is one of many in the canonical text that is America.

By the time the intermission came, I felt like I had lived a life – or maybe half a life.

The intermission is functional in providing a much-needed bathroom break in the midst of this lengthy tale, but it’s also divisional plotwise. Act Two, “The Hard Core of Beauty,” (a title that may be a bit too on the nose) signals the long-awaited arrival of Erzsébet and her niece Zsófia.

I have been singing the praises of Act One – it is for sure one of the strongest pieces of filmmaking of 2024.

Act Two is still good, but Corbet’s confidence does give way to a bit of floundering here.

The Tóth family’s arrival signals the slow fraying and unraveling of the tightly-wound promise of the American dream. It’s a standard two-act rise-and-fall structure, but the expected progression of the plot doesn’t downplay the heavy hits the family faces.

Erzsébet, malnourished from the Holocaust, is now in a wheelchair. Joe Alwyn, taking a turn as Van Buren’s son: a predatory, nationalistic shadow in his father’s footsteps, makes a point that Tóth should know “we tolerate you.”

And in a case of textbook capitalism, Tóth declines pay in order to keep budgets in line with his artistic vision.

The negatives keep piling onto Adrien Brody’s shoulders until the one plot event occurs that seems to turn many off of this movie. It’s definitely the weak spot; Corbet seems to fanboy over Paul Thomas Anderson a little too hard here, to the point of it becoming a bit hamfisted.

One pretentious plot choice isn’t quite enough to drag the whole movie down, though. The film recovers mostly smoothly, and the fallout from the event culminates in a scene-stealing moment from Erzsébet.

A complex and open ending, very clearly what a director like Corbet loves to leave the audience with.

Perhaps the most contention comes from the film’s epilogue, one which is sure to rile up very online debates. The ending reminds one of films like “Evil Does Not Exist” or “Enemy,” with a turn so sharp it could leave the viewer dizzy.

It opens a book of questions, floating ideas of the artist’s control of their work, who is allowed to tell its story, and it even seems to take jabs at a hot-button political issue.

Some will say “The Brutalist” is a “born in the wrong generation” flex that exists just to look beautiful and win a few Oscars. Sure, it definitely feels like that at times. I think it’s a bit more than something that shallow, though.

There’s a clear passion and nostalgia in Corbet’s use of forgotten film technology that reminds me of Andrew Nieman’s words from “Whiplash:” “I want to be one of the greats.”

Brady Corbet does not seek to emulate this sentiment with “The Brutalist;” he seeks to pay tribute, even if he doesn’t quite reach the heights of Frances Ford Coppola’s epics.

This fact makes it doubly funny that in a year with two passion projects about visionary architects, I would much rather see the ambitious up-and-comer’s film that occasionally succumbs to its own audaciousness than whatever “Megalopolis” was.

Okay, all of that is fine and well, but why tell this story in particular?

In his Golden Globe acceptance speech, Corbet spoke with urgency about the artist getting final say of their work. Perhaps the hulking, prestigious conceit of “The Brutalist” is a mere vehicle for its true story – a cautionary autobiographical fable of the artist in America.