For years now, my obsession with Bladee has been a not-so-secret not-so-guilty pleasure. It’s one of the gaps in my music taste where most people go, really? You listen to that?

Honestly and non-ironically, I find Benjamin Reichwald, known by the moniker Bladee, to be a fascinating, ever-changing artist who has created an intentional, deep mythos around himself and his work.

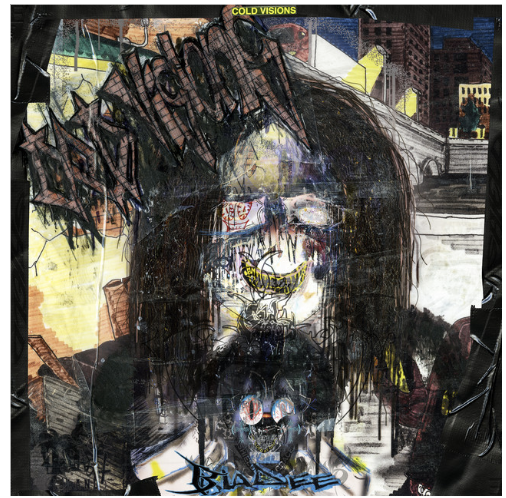

In typical Bladee fashion, he dropped his new album, “Cold Visions,” on a Tuesday night. No fanfare, no prior promotion, he just put the thirty track project out into the world.

Instantly, long-time fans felt there was something promising about “Cold Visions.” It looked like a return to form, a return to beloved albums such as “Icedancer,” and “Working on Dying.” The album features frequent collaborators like Yung Lean, Yung Sherman, Thaiboy Digital, Black Kray, and Sickboyrari.

For those unfamiliar with the Swedish artist, Bladee is the key member of a collective called Drain Gang. Fans call themselves Drainers, the music is Drained. The collective includes Ecco2k, who is noticeably absent from the new project, Yung Lean, Thaiboy Digital, Whitearmor, and Yung Sherman.

The group began in Stockholm in 2013, with Reichwald signing to the independent Swedish label Year0001 and instantly making names for both him and his friends as a part of the cloud rap scene.

Reichwald spoke about the meaning behind the group’s name, saying that “Drain is about loss and gain; it could be good or bad — you could be drained of energy or you could drain something to gain energy. There’s financial, emotional and physical drains, for example — you could just be draining your bank account at the store. It doesn’t have to be deep. Basically, if I’m talking about ‘eating the night’ that means I drain it for its essence. Everything me and my bros do is connected to that concept — we might drain some blood for good fortune.”

From the beginning, there was a sense of intense camaraderie. Reichwald and his childhood friend Zak Gaterud, also known as Ecco2k, were in a band called Krossad as preteens. He then met Jonaton Leandoer, or Yung Lean, through his brother, and the two would become close partners and friends.

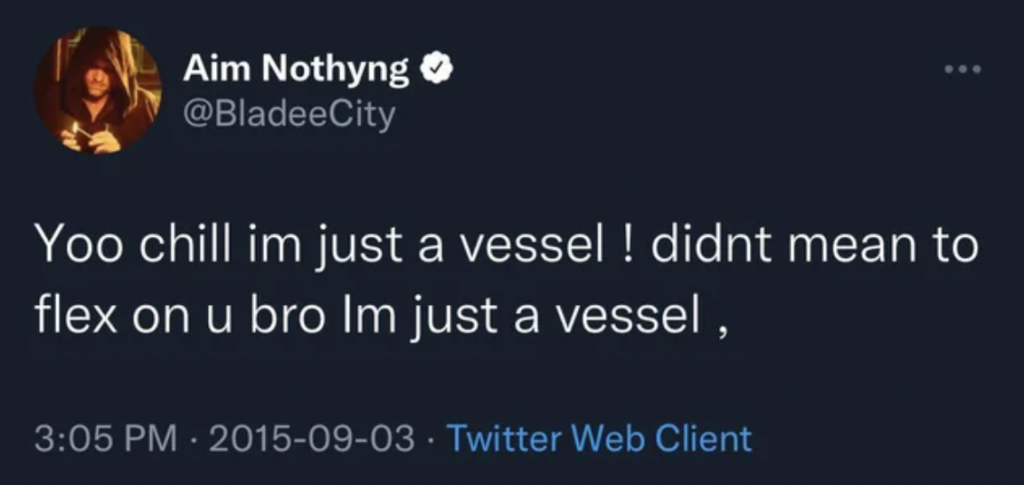

Much like my own experience, people are captivated by Bladee. For a 21st century musical artist, he is shockingly private. He rarely does interviews, and his social media presence is cryptic.

A classic tweet from Bladee’s strange digital footprint

In a rare conversation, Bladee said that he doesn’t like Instagram or Twitter because every time he tries to express himself “People reply and they missed the point of what I’m trying to say.” He follows up, “I feel like I have something more to offer now, and I can put you on to something new and teach you something.”

You might ask, what is Bladee trying to teach me? I’m not exactly sure. It is my underlying gut feeling that he does have something to teach us which has driven me to write this as a sort of investigative process, as well as a review of his new album.

Delving deeper past the mystique, the dichotomy of the positive and negative aspects of the term Drain is constantly present in Reichwald’s work as Bladee. He deals in juxtapositions, fascinated with symbols of brightness and making them dark in some way.

There are also Bladee’s compelling motifs, involving fashion, an expression of femininity, and continued repetition of the images of female tropes in his writing.

The two predominant tropes that appear are the ‘popular girl,’ and the ‘princess.’ He continuously identifies as both an outcast and a shapeshifter, or a seemingly perfect figure with dirty, dark secrets.

On “Cinderella”, Bladee sings, “Your glass shoe don’t fit, we gon’ steal ‘em,” and “Feel like 16, but I’m not that sweet.” This comes off the 2017 project “D&G,” which was a collaborative effort between Bladee and other Drain Gang members.

Even before this, fairytale sentiments appeared in his work, like off of “Eversince,” in 2016, where he croons “I can’t take the truth today / So tell me a fairy tale,” during the song “Sugar.” From the same album, “The first born got his world torn / I came out of the ice storm.”

This surprisingly romantic imagery haunts me. I am torn between the belief that he is spinning an elaborate fairytale, fit with the Bladee persona as a tragic main character, or that these images are a simple aesthetic accessory that acts as an instrument of worldbuilding.

Part of me wants to recognize his themes as characteristic of the recurring obsessions of an artist. I’m not sure I consider him an artist. I’m not sure what I consider him. And here, we return to what is simultaneously compelling and repelling about Bladee as a creator. Is any of this serious? Is it worth reading into? In an age of internet irony and humor built solely around satirical acts, what is Bladee trying to tell you, trying to tell me?

Perhaps there really is nothing beneath the surface, and all interpretations of his work serve simply as speculation. In some ways, I bask in the freedom of my uncertainty of Bladee’s work.

He never tells us what to think of him, and yet he has a very defined visual and lyrical style. This is uncharacteristic of the hardly subtle messages of much of today’s media. Bladee’s message seems almost to be no message, and yet every message: you alone create your perception of the world.

As frequent as the allusions to myths and folklore come the direct name-drops of fashion lines and the association of Bladee with a very particular female archetype. I mean this quite literally , as Bladee has a song called “It Girl,” and a song called “Mean Girls,” which are both on the same album.

From Oakley to Fendi to Gucci, he directly and frequently advertises popular brands. Additionally, the location of the mall is brought up constantly in his work: “Hit the mall and I sunshine,” from “Spellbound,” “I’m a mallwh– and my Pradas look like Tom Ford’s,” from “Mallwh– Freestyle.”

This repetition has more easily traceable origins. Bladee commented that “This world and material things – it’s all trash. The only true worth is what’s inside you, man. The rest of the [stuff] is just trash. The world is a trash island. You have the power to create your own reality.”

For an artist who references a brand in nearly every song and whose outward persona is built partially around wearing those same brands, this statement is slightly confusing. It leads me to think that Drain Gang is simply all a joke, an elaborate commentary on capitalism and consumption. But I’m not so sure.

Reading interviews with other members of Drain Gang such as Yung Lean and Ecco2k, the impression I get is thoroughly genuine. They enjoy fashion and expressing themselves in a manner true to themselves.

So where does the art separate from the artist? Where does Bladee begin, and Benjamin Reichwald end? While I know soundly that Bladee and Reichwald are two different entities, I don’t know whose style is whose.

The easiest answer is probably that they are a manifestation of each other, fairytale bleeding into reality, or vice versa. Art imitating life. Life imitating art. Either way, the confidence of Bladee’s presentation and my confusion as to what it might mean is what brings me to return to his music, again and again.

There is a Yung Lean quote that feels important to close with. He said, “I think you shouldn’t get my music confused with who I am, because Yung Lean, from the beginning, is a character created by me. Yung Lean was everything [I] wasn’t. And so me, as a person, my views on things are certainly different from Yung Lean’s views. You should definitely not get those two mixed up.”

In some ways, this answers my question. In a lot of ways, though, it doesn’t. Yung Lean is independent of Bladee. While they are both part of the same group and their messages and themes intertwine, the imagery of fairy tales and femininity is specific to Bladee’s music.

Regardless, it is sage advice for beginning to deconstruct his persona. Any interpretation of Bladee is entirely subjective to the listener. The one message that is clear, I think, remains to be that the construction of your own universe is possible.

On the much darker flip side of these lighter themes and the search for meaning comes the presence of mental illness and addiction. In the song “Decay,” he muses, “I wonder, why am I alive?” Similarly, in “Wrist Cry,” there are the lyrics, “The blade is on my wrist, it makes it cry, make it cry / I feel like I could die / I feel like I don’t care if I survive.”

So, in the background of glossy production and princess tales, there is that drainer dichotomy again, dark and light.

This sets the stage for “Cold Visions,” which seems to build upon those struggles with depression and drugs, painting a unique picture of Bladee’s inner demons.

On the track “Wodrainer,” he sings, “So much designer, got sick of that / So much designer, we been in that / Put it in the trash, we binning that.” This implies his increasing displeasure with the celebrity realm, with money and fame. It also marks a separation from his aforementioned obsession with name-dropping brands and labels, a seemingly authentic sign of maturity or change.

And then, more directly, “Sleep is the one time I’m happy.” The lack of sleep pattern continues, as Bladee extrapolates on the track “Terrible Excellence.” He delivers the lines plainly: “I haven’t slept for a week, I can’t sleep / I’m having anxiety, I can’t breathe / Bad feelings, I’m hooked on the bad feelings.”

Throughout the album Bladee also references consumption, talking about how addiction has ruined his ability to enjoy day to day life. On “Don’t Do Drugs,” he delivers in his usual half-singy-songy half-direct tone, saying that “having issues with drugs,” makes his “reality pale.”

He also alludes to a conversation with a friend struggling in a similar vein: I told my bro, “You gotta stop” / And he told me, “But for what?” / Man, I don’t know.”

If these lyrics are in any way truly reflective of what Reichwald is dealing with, it’s concerning. He can see the issue, he can reach out with compassion to someone he cares about, but he has the same hole to fill and cannot answer why it would be worthwhile quitting.

Meanwhile, scattered among the tracks are call-backs to his previous works through repeated lines and imagery. Again, on “Terrible Excellence,” he says he’s “eating the night,” which is also a line in the song “Nike Just Do It.” Then, on “One Second,” there is the line “Back of the club with the mean girls,” which directly references the 2020 song “Mean Girls.”

So, while focusing on these darker themes of depression, drugs, and a struggle to connect with reality, Bladee is also re-visiting his prior work, elevating it with harsher production that feels like a shock to the system.

There is something deeply concerning here. A man renowned for his mystique, his aura of intangibility, his enigmatic visuals and modes of communication with his fans, is being real. No touch of irony, no question about what he is trying to tell us.

Then, there are the lines that have made fans speculate that Bladee is saying goodbye.

On the second to last song of the album, “Can’t End On A Loss (Outro),” he sings, “Tell me when to quit, if this not it.” This lyric is repeated over and over. Thank you for everything,” he continues. “But you know what’s going on with us / Thank you for hearing me out.”

The entire project has brought the listener here, to the finale, painting a portrait of addiction and mental health battles and disenfranchisement. When he says, but you know what’s going on with us, it seems to me to be an invitation to go back through the album, to sift through the signs, to recognize he is facing an intense crisis. Additionally, its self-referential nature can look like a sort of goodbye tour through a lens, re-living all the greatest hits of his discography.

As a person who loves to look for symbols and meaning, Bladee’s music has provided me with a rich ground for exploration. He is simultaneously fun and serious, light and dark, feminine and masculine. If this is goodbye, Reichwald will always hold a special place in my heart, and I will always defend my enjoyment of drain gang vehemently.

Top Tracks:

- “Flatline”

- “Terrible Excellence (feat. Yung Lean)”

- “Lucky Luke (feat. Thaiboy Digital and Yung Lean)”

- “Bad 4 Business”

- “Message To Myself”