It’s no secret that there are some hard facts no one likes to think about. One of those facts is the truth of the world, that there is violence which persists daily, people who go without, people who suffer and are turned away by society. This is a fact which many people choose to ignore from the safe bubbles of neighborhoods or college campuses.

Yet, this fact permeates. It’s hard to truly ignore, it’s always there. In the news, on the street corners, in the lived experiences which we try to push down and move past, injustices people have overcome, injustices people still face.

The author William T. Vollman does not shy away in the face of harsh reality. He embraces a unique standpoint which is most likely why he was overlooked in the face of most of his contemporaries.

Or, perhaps his obscurity is due to the fact that his novels are incredibly daunting: typically over seven-hundred pages long and incredibly dense. They cover difficult themes, too, covering narratives about the typically unwelcome sides of life.

In March of this year I finished Vollman’s book called “The Rainbow Stories.” It’s a collection of short tales and a prime example of these themes, with each piece focusing on the world of so-called undesirables. Murderers, skinheads, prostitutes, engineers pushing the boundaries of what is human and what is machine.

He explores these topics with resounding empathy, giving full lives to those who appear in his stories, often focusing on unhoused individuals or young people facing difficult situations in abusive relationships or all too quickly being indoctrinated into troublesome ideologies.

Through this empathy he touches on the human condition with great understanding and generosity. How we come to be who we are, how we develop as people. Vollman does not turn a blind eye to what many regard as filthy, dirty, unromantic, or unkind.

Still, his writing is immensely difficult at times to get through. It’s dark, depressing, and confronts the reader with an honest view of transience and lack of meaning in the world.

Through Vollman’s career I arrived at the writing of the anthropologist Mary Douglas. In her seminal work Purity and Danger: an analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo, Douglas asserts that societies use concepts of cleanliness and purity in order to create and maintain order within social structures.

Vollman’s characters are significantly outside the realm of what Douglas, and most people, would classify as clean. We want so badly for things, and people, to fit into neat little categories, and Vollman wonderfully embraces everything outside of that.

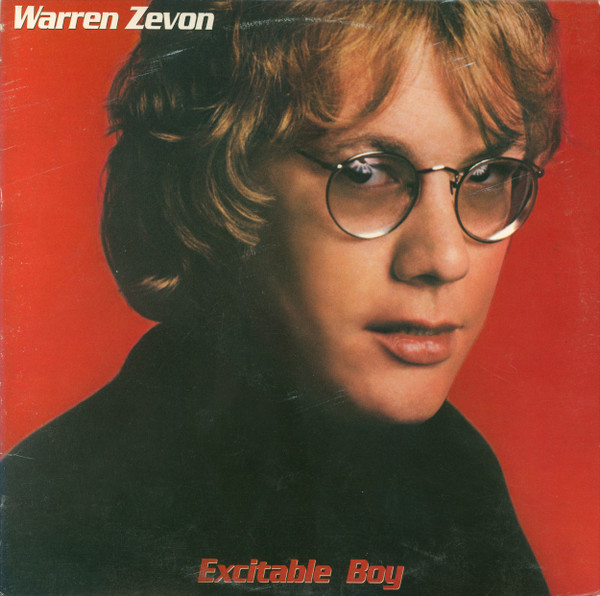

So, with all of this on my mind, listening to the brilliant album “Excitable Boy,” by Warren Zevon conjured images of both Vollman and Douglas within my mind.

Zevon was somewhat of an undesirable character himself. He was a smart child, somewhat of a prodigy, who grew up in a fractured household with an immigrant father who was a bookie for a notorious gangster and a Mormon mother. At sixteen, he dropped out of high school to move to Los Angeles and seek a music career.

Zevon failed to get a foothold in the music industry for a long time as a song-writer for hire, writing two songs that would be performed by the band “the Turtles,” and putting out a disappointingly-received debut album. However, with a powerful friend on his side, the renowned Jackson Browne, Zevon signed a record contract.

He had a number of powerful, or soon-to-be powerful friends. Bonnie Raitt, Fleetwood Mac, members of the Eagles, and the Beach Boys all backed him up on his finally successful 1976 album “Excitable Boy.”

Running alongside Zevon throughout this whole experience were his struggles with drugs and alcohol. He was a notorious figure, always showing up to the recording studio drunk and maintaining multiple relationships, simultaneously pushing away his wife, Crystal, and their children. Most people knew him as such. Still, he was kind beyond his demons, whip-smart, and well-read.

This core ‘undesirability,’ is reflected in Zevon’s chosen focus material for his songs. They revolve around addicts, gamblers, killers, soldiers with questionable motives.

With ease, Zevon turns the darkness of Vollman’s self-same characters into seemingly light-hearted songs. It’s only when delving into the lyrics that the truth becomes more apparent.

Take the lyrics of the titular song from the album, “Excitable Boy.” It’s story revolves around a young kid whose ever-increasing acts of violence in each verse, from spilling pot roast on his Sunday Best to murdering a girl, are continuously overlooked by a society who either incredibly desensitized to the acts or desperately wants to ignore them and return to a state of normalcy.

Then, there is the woesome account of “Lawyers, Guns, and Money,” which features a gambling protagonist who is always on self-inflicted hard times, refusing to take responsibility for their actions. Zevon sings, “I was gambling in Havana / I took a little risk / send lawyers, guns, and money / Dad, get me out of this.”

Of course, I can’t leave out the most famous song of all. “Werewolves of London,” portrays those you might want to avoid on the street at night, the stalkers and hedonists who will mug you just for fun, the prime examples of an undesirable.

The song was written as a joke within fifteen minutes while watching horror movies, and Zevon did not want it on the album. He believed it was not meaningful enough.

However, Browne advocated for a more kind interpretation, saying, “It’s about a really well-dressed, ladies’ man, a werewolf preying on little old ladies. In a way it’s the Victorian nightmare, the gigolo thing. The idea behind all those references is the idea of the ne’er do-well who devotes his life to pleasure: the debauched Victorian gentleman in gambling clubs, consorting with prostitutes, the aristocrat who squanders the family fortune. All of that is secreted in that one line: “I’d like to meet his tailor.”

It seems that with the commercial success of his songs, Zevon has effectively reconciled the dark underbelly of our society with a larger audience. He takes what is strange and makes it clean and polished with his deep voice, his wonderful piano playing, his excellent band and the melodies that they carry.

Of course, Zevon was not broadly accepted by the public, and not always commercially successful. His gleeful singing about murder in “Excitable Boy,” shocked most people. He was still a slight celebrity, mostly known for the song “Werewolves of London.”

Yet, in a time where the mainstream audience preferred virtuous music, Zevon’s outlaw figure was brave and brash in the face of his critics. His music provides a danger and romance outside of everyday life that flips Vollman’s mostly inaccessible figure of the so-called undesirables on its head.

Zevon’s injection of humor and tongue-and-cheek irony makes each of his chosen outlaw subjects suddenly desirable, suddenly in on the joke instead of being the joke. We as the audience are not laughing at the characters, we are laughing at the society that is reflected, laughing at ourselves.

For instance, “Excitable Boy,” is not about the boy so much as it is about the people who ignore and allow for the boy’s behavior. “Lawyers, Guns, and Money,” is making fun of a legal system that allows for a rich kid to get out of his close calls by simply phoning his father.

And then there is Zevon’s philosophy, which also goes against the grain. In the song “I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead,” Zevon sings about a man who refuses to stop living life to what he perceives as the fullest, drinking and partying. It’s ripe with cynicism and morbidity, and the song title was even used as the name for his anthology album and a book written about him posthumously by his wife.

“Saturday night I like to raise a little harm / I’ll sleep when I’m dead,” Zevon sings. He also comments that if he starts acting stupid he’ll commit suicide, driving home a stark indifference about his actions and their consequences.

Whatever Zevon did, he did it as an undesirable. He effectively took the impure, the un-categorizable, the things we like to overlook, and gave it an outlet and a voice. Listening to Zevon’s music is staring into the void, one of pain and suffering and pointless actions, one that defies our need to organize and feel safe. He was an incredible musician and figure and I am confident that the themes of his work will persist throughout all of time, reflecting the world many try to look away from.