There’s just something so appealing about “Columbo.” Maybe it’s Peter Falk’s rumpled brilliance portraying this character, from his coat to his hair, or the dog named “Dog,” or the inverted concept of a mystery story as a howcatchem instead of a whodunnit.

Now, I have a long history with on-screen detectives. I love the unreliable narrarators, the scandal, the often sleazy environments. The first season of “True Detective,” has one of my all-time favorite characters in Rust Cohle. One of most-watched movies is “The Long Goodbye,” which features Elliot Gould’s amazing portrayal of the private eye Phillip Marlowe. My mom and I have watched nearly all twenty-five seasons of “Midsommer Murders,” religiously, with cozy blankets and cups of tea in hand. For me not to fall in love with “Columbo,” would be like a dog not wanting a bone.

I was introduced to the show only a week ago, as a friend put on an episode for us to watch. Needless to say, I was instantly hooked.

One aspect that is so entrancing about the show is the score. Though “Columbo,” has no official theme song, in each episode there is a variety of music by accomplished composers that creates a unique feel. Over twenty-one composers worked for the show over the course of its air time, with the most well-known being Quincy Jones, Patrick Williams, Harry Mancini, and Billy Goldenberg.

While there was no official theme song, Mancini recorded “The Mystery Movie Theme,” which occurred in about thirty-eight episodes of “Columbo.”

The theme is punchy and bright, with soaring piano and a searing synthesizer accompaniment. It feels very optimistic, full of fun and excitement. Mancini wrote the song for a series of four shows of which “Columbo,” was a part of, occupying all of NBC’s mystery movie programs.

Other than this recurring tune, there is the old kid’s song “This Old Man,” whose eerie rhythm Columbo often hums in the background. This was in actuality just a song that was stuck in Falk’s head while on set one day, but it slipped into the final cut. Fans became so enamored with the motif that it was picked up as one of Columbo’s quirks. It was also added to score arrangements in the opening and closing credits, including a version of the song “Columbo,” composed by Patrick Williams.

With the lack of consistent music came innovation in the works of the musicians. Each score contributes specifically to each episode outside of the realm of “The Mystery Movie Theme,” to build exquisite tension and specifically work alongside the narrative.

An example of this is in the episode “Etude in Black,” where the score is particularly excellent. It was done by Dick DeBenedictis, who is notable for his multiple Emmy nominations due to his work on a number of other popular television shows of the time.

The episode is notorious among Columbo fans, many of whom regard it as their single favorite episode, and many who find the central mystery and driving clue too weak. To me, however, the episode is perfect.

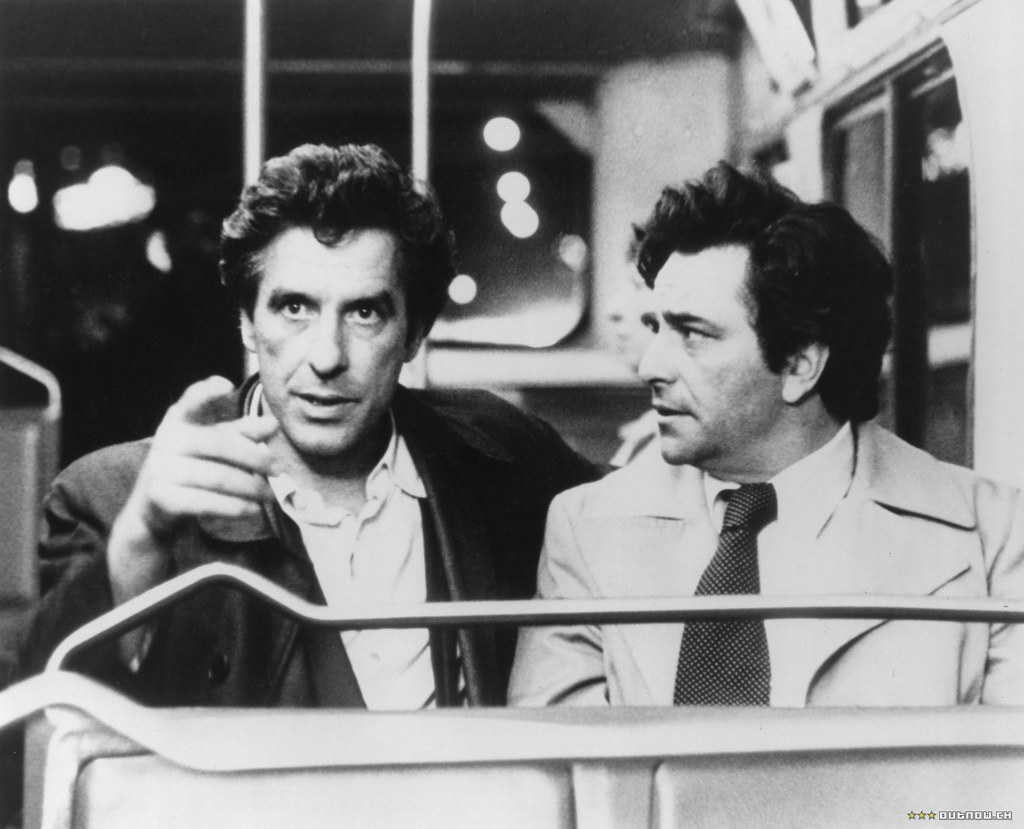

It revolves around a renowned orchestra director named Alex Benedict, portrayed wonderfully by the charismatic John Cassavetes, who will lose his fame and marriage if his affair with a young pianist in his band is exposed. So, he kills her, covering it up to look like a suicide.

Of course, Columbo suspects the murder is not all that it seems, and immediately suspects Benedict. The episode ensues with the tracking down of clues and inconsistencies as Columbo pesters the director constantly with his questions. It turns out that Benedict has left his distinctive lapel flower, a pink carnation, at the scene of the crime, which is how he is eventually discovered.

Behind the story is the score, weaving in and out, simultaneously complementary and individually engaging. It’s dark and eerie, nothing like the previously mentioned theme song, displaying the range that “Columbo,” music occupies. There’s a strange gong in the background, an escalating bell sound, and single piano notes that create a deep sense of unease.

Aside from the music, there is something to be said for the somewhat surreal realm of murder mysteries “Columbo,” occupies. Unlike a show like “True Detective,” which grounds its killings in a depressing and dismal reality, “Columbo,” is posh, elevated, and marked by massive amounts of wealth. Nearly all of the murderers depicted on the show are fabulously rich or at least in distinct positions of power. They are successful orchestra directors, best-selling authors, famous stage actresses, or accomplished politicians. Further, the landscapes of the show are similarly extravagant, showing crystal clear blue pools, expansive gardens, and sprawling mansions.

“Columbo,” deals with what I want to call silly murders. It’s violent and cruel, sure, but the violence is downplayed and there is never a great display of blood or destruction. The focus is on the mind game between the villain and Columbo and not the real-life ramifications of such actions. People kill for seemingly more easily resolvable issues, like infidelity or control of a company.

Perhaps it could be argued that “Columbo,” is a commentary on the whims of an upper class who feel that their actions will never be punished, that they are above the law, and the character of Columbo serves to bring them to justice. He certainly is always portrayed as more lower class, with his disheveled appearance which many take him less seriously for, exposing in “Etude in Black,” that he makes 11,000 dollars a year, which is now around the equivalent of 77,000 dollars, noticeably far below the income of the people he investigates.

The philosopher Adorno wrote in his chapter “How to Look at TV,” about exposing the hidden socio-psychological mechanisms that are at work in television in order to enforce social norms.

He claims that popular culture is at work in all forms of media, and following most American’s desires to feel safe, stories about inward conflicts have turned into unproblematic and cliche storytelling with no variation. Television has become about securing viewer numbers and pacifying audiences, not artistry. Further, every story is a complicated layer of hidden meanings which serves to handle the audience and expose them to covert messaging.

I think that “Columbo,” is working within Adorno’s criteria to quietly subvert these socio-psychological mechanisms against the norm. On one hand, each episode has a simple and unassuming framework: a murder happens, Columbo shows up, instantly knows who it is, and spends the rest of the run time trying to pin down the killer with sufficient evidence.

However, on the other hand, there is latent messaging at work here, proclaiming that murderous people who presume they are too clever to get caught will never get away with it. If you are deceitful, petty, quick to anger, and egotistical, you will be tracked down by the likes of Columbo, a man whose very being embodies the opposite. You should be more like Columbo, who represents the antithesis to the privileged upper class the show illustrates.

He is kind, fastidious, concerned with matters of right and wrong, and unconcerned with worldly goods or high-quality items. He has worn the same jacket for seven years, eats simply with a diet chili and black coffee, and is unaware of culture mistaking a ventilation grate for a piece of fine art.

The show warns you against the indoctrination of a wealthy lifestyle that leads to an inflated sense of self-importance and a removal from the truth of most of working class society. While wealth and decadence is typically portrayed as positive, “Columbo,” approaches it through the lens of violent crime to create an air of cautionary class consciousness that resonates silently with the viewer.

That being said, Columbo is still a cop, and there is a power that comes with that position that must be recognized. He is not clean in the eyes of Adorno’s propaganda, as he is portrayed as a good cop, and in turn suggests all cops are as good and concerned with justice as him.

All the same, with its cerebral storytelling and Falk’s charm, “Columbo,” will surely be a show I return to over and over again. The program represents a time in television that contestably has been lost, relying on the audience’s patience as the story unfolds, with no big action and lots of mindful observation required. The music, too, reflects a careful attention to detail that I sorely miss each time I turn on a new Netflix show in an attempt to get hooked in the same way. It’s deliberate, beautiful, and memorable.

As I walk to class, I find myself humming “This Old Man,” just like the clever detective.