In the days after my cousin died, things were chaotic. We gutted her apartment, tossing the groceries that had been left to rot on her countertops — she’d had them delivered, but never made it home to put them away — and sorting through boxes and boxes of glittery soaps, salves, tinctures and ointments.

My extended family, worn out both from the flight down here from New York and the drive down to Myrtle Beach to claim my cousin’s body, had us trash most of it.

Over the course of two days, the dumpster filled with more and more of my cousin’s things: garbage bags packed almost to splitting with sunglasses, costume jewelry and random, unused items from television ads that had long gathered dust.

My youngest brother uncovered a custom hookah shaped like a badazzled machine gun, and lamented as our mother (“hell no! absolutely not!”) refused to let him keep it. My other brother found a lockbox filled with “miscellaneous pills and powders,” which he quickly resealed. The key (with a fob reading “Italian Girls Have More Fun”) remained jammed inexorably into the keyhole.

We didn’t throw away everything. While my living cousins made off with designer bags, photographs and a glass-blown pineapple-shaped bong (“for sentimental value,” one cousin stressed), I found myself gravitating towards stranger things. Bric-a-brac, tchotchkes and glorified trash.

A box of rave kandi. A bottle of orange liquer shaped like a dachshund. An old ID from the community college she’d dropped out of in 2006.

After we emptied her apartment, everyone went back home. My grandparents and great aunt flew back to New York. One of my cousin’s long-time friends came and collected her bereaved yorkie. I went and took my board-op test to become a DJ. They had the memorial service up in New York and everyone got stoned (or so I heard.) So it goes.

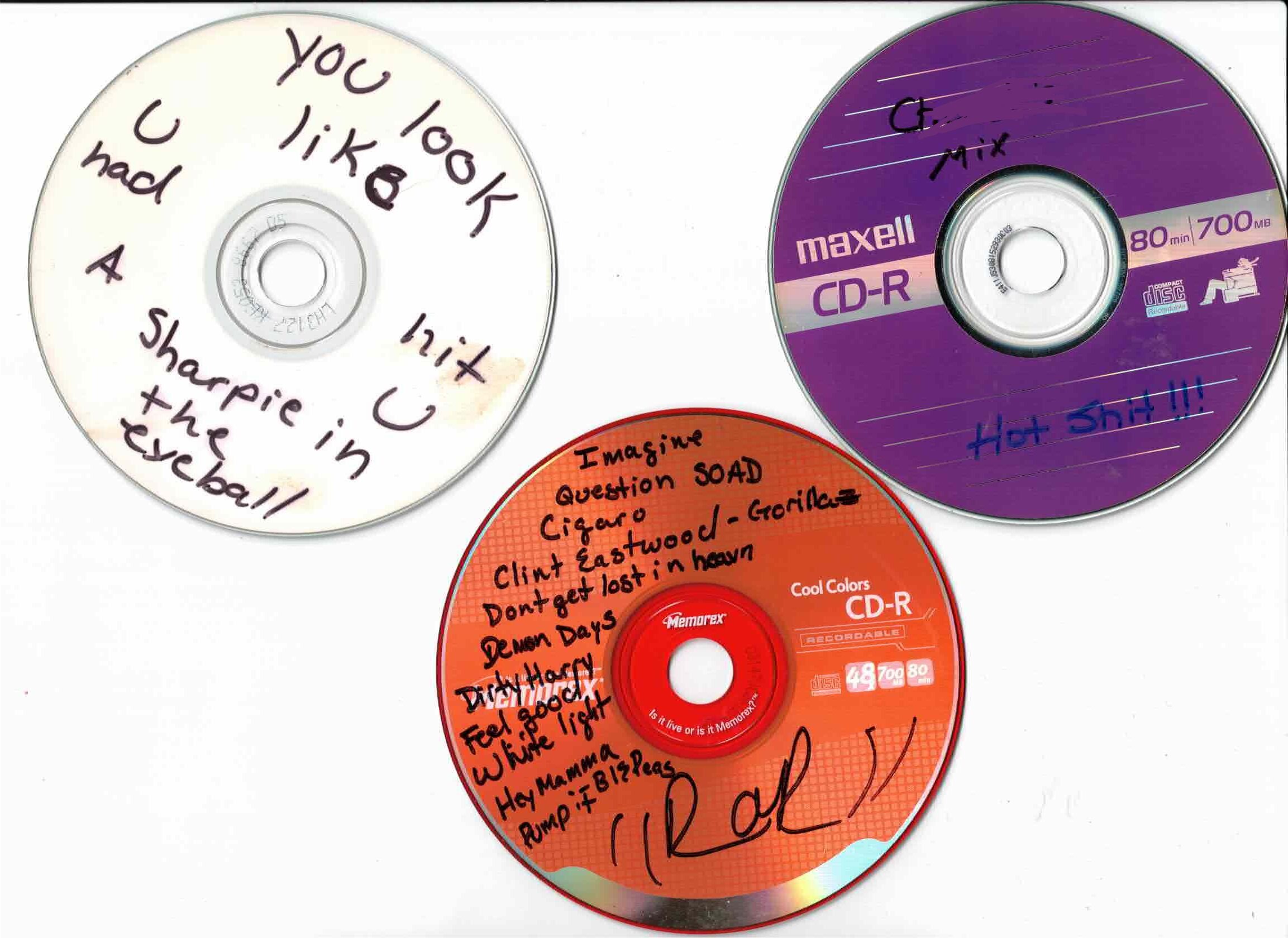

Somewhere along all of this (it all feels nonlinear to me, like skipping through a movie in 10-second incremends), I ended up with a bag of CDs.

“Here, do you want these?” My mother held them out like one does a dirty diaper, pinching the bag (it was one of those plastic sleeves people keep duvet covers in) by the corner so the CDs puddled in the bottom. They were loose and probably scratched to all hell; probably unusable, really; probably trash.

I took them anyways, stuffing the bag under my bed to rot.

Over two years later (specifically, March 30, 2024), I decided to finally work my way through them. Here’s what I learned:

Laying Out the Particulars of My Inheritance

Parsing through my cousin’s CD collection was like cracking open a time capsule from the early 2000s. As I sat on my bedroom floor and fed disc after disc into my cheap CD player, I felt like I was talking to her — and my adolescent self — again.

“God, you really liked Ludacris, didn’t you?” I said to someone who wasn’t there. Not physically, at least.

It was a 21st century seance, a transgenerational ceremony conducted via polycarbonate. I was channeling my cousin’s spirit, and rather than imploring her to answer my burning questions (“What is life like after death?” “Did you understand what was happening?” “Are you at peace?”), I silently judged her drippingly-2010’s music taste.

Like me, she’d constructed most of her young life around music. I could trace her progression of style, the alt rock and grunge of the 90s and early 2000s giving way to the hip-hop renaissance of the 2010s.

I laid out tall stacks of custom CDs with titles like “Summer 2006,” “Hot Sh–” and “My Mix” lettered in girlish sharpie. I imagined how old she had been when she wrote them, whether or not she’d had her nails done and if her wrists were heavy with gaudy beaded bracelets.

In a time before iPods and bluetooth and — heavens forbid — Spotify, burning CDs was a sacred practice. Music was corporeal, and one’s affinity for the stuff became something physical — piles of CDs, stacks of vinyl, etc — that demanded real estate. By comparison, my preferred method of music consumption (streaming) seemed compressed.

In my adolescence, I myself burned songs onto discs — pirating the tracks online, then meticulously ordering them by “vibe” — and eventually did the same on my first iPod. But those were all long gone, sublimated into a single app on a phone I often misplaced.

Sitting cross-legged with a plethora of discs fanned out before me, I picked out several names: System of a Down (one of my top artists of 2023), Nirvana (also one of my top artists), Kittie, Korn, Slipknot and an obscene amount of Limp Bizkit.

I’ll be honest: I’m not all that familiar with Limp Bizkit’s discography. I’m more familiar with Fred Durst, who I’ve mentally elevated to the status of a sort of mythical folklore hero (or antihero?). Anyways, I decided to put on “Chocolate Starfish and the Hot Dog Flavored Water” and was utterly shocked by how awesomely stupid it was. It’s great.

I could imagine my cousin, a teenager or perhaps in her early twenties, speeding down the highway in her little blue SUV and cranking the radio up to full blast, singing along to Fred f–ing Durst and reveling in the invincibility of youth and the heat of a seemingly endless southern summer.

I’m a renegade riot gettin’ out of control

“Livin’ it Up” – Limp Bizkit

I’m a keepin’ it alive and continue to be

Flyin’ like an eagle to my destiny

So can you feel me? (hell yeah)

Can you feel me? (hell yeah)

Can you feel me? (hell yeah)

Transgenerational theory posits rules for the ways in which rrituals, practices, behaviors and philosophies move down generational lines.

Think transgenerational trauma: agony passed down from grandmother to mother to daughter over three lifetimes. Her mother was my mother’s aunt, second eldest of seven first-generation Italian immigrants. Evidently, not a fan of Fred Durst or Serj Tankian or any of the other yelling men my cousin liked to listen to.

And while the CD collection made its way into my hands (unceremoniously, I might add) intergenerationally (i.e., it was literally passed down), the physical discs themselves weren’t the only thing I was given. There was something else in transference, something intangible. A transgenerational impulse.

Energy, maybe. A parasocial connection to a teenager I’d never met who grew up to be an adult I loved and lost, a teenager who probably wasn’t much different (if anything, less emo) than my own teenage self. A teenager who meticulously curated mixes for each season, each new year, each new release.

I pop in a disc without a name — it’s hazy green on the front — and watch it spin, and instead of frenzied guitar and drums, I hear a delicate strumming and familiar, dreamlike voice.

I don’t miss you

“Soothe” – Smashing Pumpkins

I don’t wish you harm

And I forgive you

And I don’t wish you away

Away

Away

It’s “Soothe,” a demo tape by Smashing Pumpkins. I’ve never heard it before, but for a moment, I can imagine I’m my cousin: young, alive, lounging before a CD player. For a moment, two dimensions in time: mine here and hers there, run parallel.