This is part two of a series on the birth of avant-garde music. You can read this article alone or view part one here.

Alright, so we spent part one introducing the topic, now it’s time to get into some specific music. Today we’re going to look at the earliest precursors to modern noise music: modernism. These composers still thought of themselves as part of the classical canon but listening to their music….well let’s just say it’s a little “out there.”

Modernism is a term used in art history a lot. Now I didn’t pay very much attention in high school English, and in visual art I have the taste of toddler, but Wikipedia confirms my vague recollection that modernists sought to replace old forms of art with newer and more exciting forms that reflected a modern, industrial world. This resulted in some notable artists like Pablo Picasso, Frank Lloyd Wright and Georgia O’Keeffe. In literature, this resulted in writers like Virginia Woolfe and James Joyce, who I’m sure some psychopathic English major actually enjoys.

So, with these beloved figures of art and literature attached to the word modernism, surely there are some fondly remembered musicians from this period? Well, no. Modernist music was roundly rejected by literally everyone. Audiences routinely rioted at modernist concerts and even through today no one actually likes it.

THE END.

Okay, that might be a little harsh. A more accurate way to put it would be that audiences don’t really know what to do with modernist music. The composers associated with the era, Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Satie, Shostakovich, wrote very difficult music that eschewed tonality and easy-to-digest sounds, opting instead for novel forms of composition that pushed the boundaries of what music could be.

The result is that modernism is the oldest Western music that doesn’t feel like classical or folk music. It’s so unconventional that it just kinda sounds like, well, noise. Take Schoenberg for example. Schoenberg didn’t like classical harmony, and he wanted to write music that lacked a key and favored no particular note as a harmonic center. To accomplish this, he organized all 12 notes of the chromatic scale in a random order called a set, and then layered the different notes backward and forwards in different octaves and on different instruments to create something that could, arguably, be referred to as music. His masterpiece, the opera Moses und Aron, is absolutely terrifying, as exemplified by this production featuring an underwear Moses for some reason.

However, you would never really mistake Schoenberg for modern avant-garde music either. He still composed for orchestra, piano, and operatic voices, it still features conventionally defined notes, and there aren’t really any of the mechanical banging and scraping sounds that typify noise. It’s too rigid and formal to be genuinely fascinating, but too weird to be good on its own. This is what I mean when I say no one really likes modernism. Classical musicians end the common repertoire right before modernism, and experimental pop listeners don’t find it edgy or daring enough. Modernism, in my opinion, is best approached as a historical document, and a demonstration of how hard it is to push the envelope of music. When you’re steeped in a certain musical tradition, the boundaries of the system can start to feel natural, rather than limiting, and the formation of experimental music took genuine imagination and work. Your toddler might be able to make experimental music, but you might struggle.

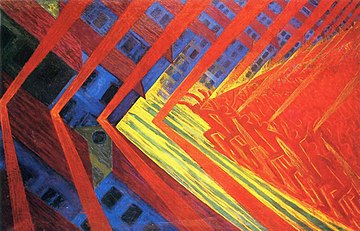

The exceptions to this rule are Russolo and Satie, the only modernists who I can enthusiastically recommend. Luigi Russolo, who was associated with the Futurist movement in Italy, made straight-up noise music. Like it would sound completely normal released today—he just tried to impersonate the sounds of steel mills warming up. Futurists were not merely extending the classical cannon like Schoenberg; they were rebelling against it. Satie, by contrast, wrote tranquil piano music that sounds beautiful, but had such a simplistic and amateur quality that his music anticipates the ambient and minimalist movements of the 60s and 70s, which we will get into later. If you want to hear the very earliest inklings of musical rebellion, these are the two artists I would recommend.