John Prine died last year, and since then his star has risen dramatically. He was already a legend in alt-country circles, but his wider legacy hadn’t been secured until the honestly surprising wave of attention given to him after his death. He’s rapidly joined the ranks of Dolly Parton and Johnny Cash as one of the handful of country stars it’s cool for indie kids to say they like. I’ve seen him tributed by country legends, indie critics, and even the Viagra Boys (can’t believe that happened), which spurred me to check out more of his back catalog. Long story short, he deserves the hype, and I strongly encourage you to give both his first and final albums a listen.

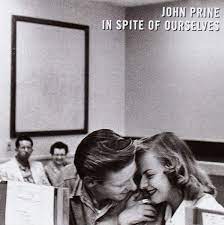

But today, we have an album from the dead center of his career, 1999’s “In Spite of Ourselves.” The album has neither the sarcastic wit of his early career nor the darker ambiance of his later career. In fact, this album is probably one of the corniest things I’ve ever heard. It’s is a full duets album with several women of various levels of fame, and almost to a one, every song is a pun-laden and silly as possible.

This isn’t really an indictment, the album is not going for high art. In fact, it works as a neat refutation of some of Prine’s more self-serious folk revival work. This is not aimed a bougie college students from Brooklyn who want to listen to protest folk singers, this is shameless middle-aged country music for people who want to listen for fun, not to feel smart. The title track, In Spite of Ourselves, has the structure and style of a straightforward Dylan love song, it could almost be mistaken for “Love Minus Zero” or “It Aint Me” if you ignore the words. If you pay attention, you’ll be treated to such lyrical miracles as “He ain’t got laid in a month a Sundays, caught him once and he was sniffin’ my undies,” and “She thinks all my jokes are corny, convict movies make her horny.” This is where I would like to inform you that Dylan himself called John Prine and his writing “Pure Proustian Existentialism.”

Sure Bob.

The utter lack of dignity on the record has a direct function though. The album opener “We’re not the Jet Set,” draws the explicit connection between the self-serious pretension folkies like to shroud themselves in and class. Prine is writing to working people, which sometimes means he uses complex metaphors for serious topics, but just as often it means saying that your wife is hotter than the Easter Bunny (the highest bar one could possibly set). The point of this isn’t to discredit the invariably northern liberals who have somehow come to be the dominant tastemakers in Southern folk music, Prine himself made no secret about being anti-war and he was originally championed by Yankee critic Roger Ebert. The point here is to uplift elements of country music that usually get a bad name, its corniness, its sincerity, its preoccupation with small-town pride.

Criticism of country music is very often valid, especially in a modern context, it can be horribly jingoistic, misogynist, and often painfully lame at the same time. But when these criticisms take a more general turn, we can sometimes fall into a kind of rank elitism, often classist snobbery, at the music of ‘white trash’ for not being “serious” enough. I’m guilty of this at times too, so let me tell you nothing will break you of that sense of self-impressed judginess quicker than listening to John Prine sing about putting ketchup on scrambled eggs.

This is not Prine’s best album, but it is the one that has changed the way I look at country music the most. A lot of young people South try to distance themselves from rural America as much as possible, but on “In Spite of Ourselves,” Prine hints that maybe we reveal more about ourselves by hating country than by just admitting this is who we are.