It’s undeniable that social media has heavily influenced music.

From the recontextualization of the industry through new marketing opportunities to the pervasion of the infamous “tiktok song” phenomenon, the way we consume music — and the way certain artists rise to mainstream popularity — owes itself largely in part to social media.

Such can be seen especially in the realm of alternative music, with once underground genres permeating into the broader subcultural consciousness.

This image was originally posted to Flickr by Libertinus, licensed CC-BY-SA 2.0

Of these genres, breakcore in particular stands out.

What is Breakcore?

A “normie” friend of mine once described breakcore as “electronic music for anime fans,” which is somewhat true in describing the genre’s contemporary sphere.

However, the “electronic anime” style many consider to be breakcore is actually far removed from the genre’s original sound.

Breakcore emerged in the 1990s as the “bastard hate child” of jungle, happy hardcore, gabba, speedcore, drum ‘n’ bass, techno, IDM, acid, ragga, electro, dub, country, industrial, noise, grindcore, classical music, hardcore, metal and punk.

This auditory hodgepodge arose in response to the rise of fascism — both figurative and literal — in mainstream society. The choppy, experimental and erratic styles of breakcore spat in the face of hegemonic consumerism, capitalism and white supremacy.

With no specific melodic style, the breakcore sound derives from a mixed bag of styles “cut and pasted” from different genres to produce elaborate beats.

Major players in the early breakcore scene included Sickboy, UndaCova and Venetian Snares.

2020s Revival

Since its inception, breakcore exists as a plastic organism. Constantly in metamorphosis, breakcore is directly influenced by the time in which it’s produced.

In sociologist Andrew Whelan’s article “Breakcore: Identity and Interaction on Peer-to-Peer,” he asserts that the breakcore genre’s development is fueled by online and peer-to-peer distribution.

Thus, contemporary breakcore possesses a distinctly “internetcore” style with influences from anime, video games and pop culture.

Modern breakcore engages with a distinctly online space, often mingling with aspects of glitchcore, vaporwave and other internet-born genres.

Growing from the digital hardcore scene of the 2010s, contemporary breakcore is not only built on sound but aesthetic.

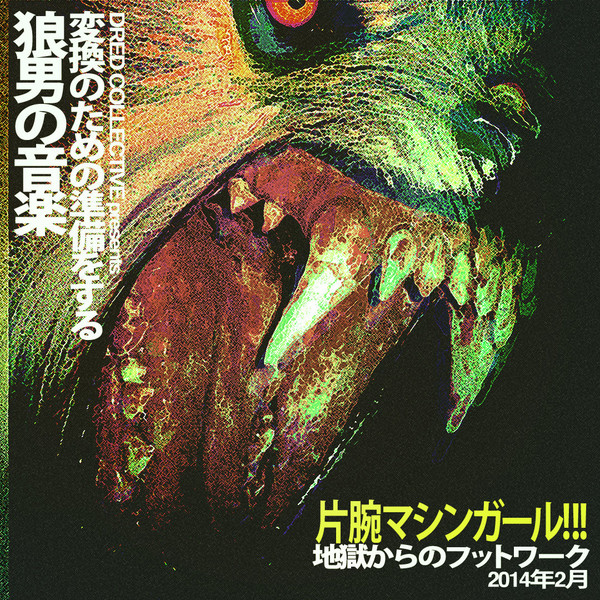

With the rise of online “aesthetic culture” and the dissemination of the “alt” label in subcultural spaces, artists like Machine Girl and goreshit capitalize on the duality of sound and presentation.

Some critics argue that this quality undermines the genre’s originally anticonsumerist convictions, with breakcore songs reaching internet virality through apps like Tiktok and Instagram Reels.

Perhaps I will cover the “tiktok song” phenomenon in a future article.

Final Thoughts

While I don’t think it’s necessarily vital to understand the history of breakcore, I do think it’s sociologically valuable.

Much like language changes over time, so does music. And for a genre as malleable as breakcore, it can serve as a sort of time capsule for the era in which it’s made.

Something about that is extremely cool to me, even if it means the genre is moving farther away from its original purpose.

Additional Reading

- Inside the experimental hardcore scene: Antifascist haven, Nazi paradise or simple absurdity?

- Demystifying the Internet’s Breakcore Revival